[ad_1]

If, in an alternate—though mostly unchanged—version of Japan, you were to peruse a certain magazine, reading carefully, your eyes might pause in their search at an ad that reads “Kamogawa Detective Agency: We Find Your Food.” No contact details or, for that matter, details of any kind would follow. But if you’re enterprising enough, you might still find your way to the Kamogawa Diner in Kyoto—a rundown building with no outward indication that, through its sliding front door, delicious food is being served to a small number of loyal patrons, many of whom have had favorite dishes from their pasts successfully resurrected by the detective agency.

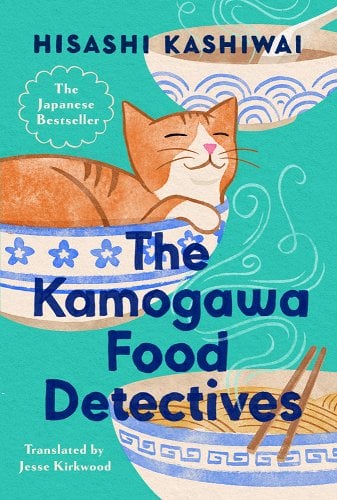

Hisashi Kashiwai’s novel, The Kamogawa Food Detectives, translated by Jesse Kirkwood, is as reliable as the comfort food described in its pages. Every chapter is named for the dish that needs finding and is broken down into sections. The first introduces the new client of the detective agency and sees them trying Chef Nagare’s food for the first time, invariably raving over its deliciousness, and subsequently giving the details of the dish they need “found.” The second section reveals the result of Nagare’s detective work: food so accurately recreated, the client is immediately hurled through time to remember vividly when they last enjoyed it and, more importantly, whom they enjoyed it with.

Nagare, we learn in the very first chapter, is an ex-police detective and thus well equipped for the task of tracking down the details of these old recipes. However, if you are hoping to see exactly how he does this, you will instead find the process of detection, though likely very interesting, is not what Kashiwai wants to leave you with. Evidence of the desired takeaway is inescapable. Nagare runs the Kamogawa Diner with his daughter, Koishi, a single thirty-something with a sizable crush on a local sushi chef who is also a diner regular. In a room at the back of the restaurant is a shrine where a photo of Nagare’s late wife, Kikuko, smiles serenely upon the life her husband and child have built together in her absence. Not a single chapter ends without the two chefs sharing fond memories of their dearly departed. In fact, more than once, the two go so far as to include her in a meal they have—choosing her favorite wine to pair with dinner and pouring her a glass, or bringing her shrine photo along on a picnic among the cherry blossoms. The enduring strength of love—between relatives, close friends, exes, or even that shown by one neighbor to another in moments when it is needed most—is at the heart of this series opener.

Like few other aspects of human life, a meal has the power to freeze a moment in time with our emotions acting as the glacier, the amber, the concrete that protects against total disintegration. Most of the detective agency’s customers remember very little in the way of a dish’s ingredients; what they can’t forget is how they felt when they ate it. One client fled the restaurant where she had the dish in question; others remembered colors from their meal; yet another did not even recall their own effusive appreciation of the food in the past and had to be reminded by Nagare of what they had said when they first tried it. It’s never truly about the food, but about the pieces of themselves each client hopes to reclaim by eating it.

As a Japanese novel, The Kamogawa Food Detectives also takes care to illustrate food’s ability to preserve a culture across generations. Tae, an older woman and regular at the diner who only ever wears kimono, gets on Koishi’s case more than once for referring to the fruit course traditionally enjoyed at the close of a Japanese meal as “dessert,” a Western phrase, rather than its proper name, “mizugashi.” No dish is explained for the benefit of readers who might be unfamiliar—every delicious morsel described is given no clarification other than its traditional name and presentation. The same is true of the streets, cities, and other areas referenced—each is given only as much detail as someone already familiar would need to locate themselves within the story. Although such familiarity can enrich certain aspects of the reading experience, it is wholly unnecessary in order to appreciate each character’s joy at rediscovering that which they had feared lost forever.

If ever you’re in the mood for the cozy, literary equivalent of a hearty stew on a cold day, The Kamogawa Food Detectives has you covered. You may end up with a craving or two of your own by the end.

FICTION

The Kamogawa Food Detectives

By Hisashi Kashiwai

Translated from Japanese by Jesse Kirkwood

G.P. Putnam’s Sons

Published February 13, 2024

[ad_2]

Source link