[ad_1]

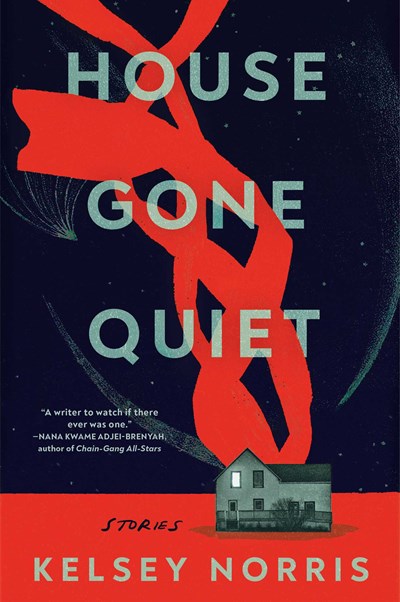

Kelsey Norris’s debut collection of stories, House Gone Quiet, tackles everything from being ostracized by one’s community, a square peg amongst round holes, to being part of communities held together by suffering, wonder, fear, and outrage. Each story’s setting is rarely explicitly stated, yet the environs feel familiar, perhaps because the experiences of the characters are all so recognizable, despite being borne of circumstances that could reasonably be called bizarre.

In the story “Stitch,” readers meet a group of ex-joggers who have all had the misfortune of coming across dead bodies during their respective runs. Subsequently, they form a support group because no one else in their lives quite understands the sensation of such an experience. But by dropping into each of their heads, Norris reveals that no member of the group feels any real connection to the others aside from the one bit of bad luck they all have in common. Each of these ex-joggers is a world unto themselves, despite being viewed, and even functioning as a unit by the story’s end. They make no effort to understand or to be understood by one another as people with rich inner lives, whose dimensions exceed the ability to stumble across dead bodies when it’s least expected, treating their fellows in much the same way the world treats their entire group. Shared experiences can be strangely isolating, as a number of stories in this collection illustrate.

“The Sound of Women Waiting” seems pulled straight from the history books. It is the story of women who have been taken from their home country to become wives to men of a rival nation. One among them, with whom the rest maintain a distance, is abused by her husband. She tries again and again to rally her fellow wives into retaliating against their husbands, but not all of the wives feel they have reason to retaliate. In fact, some of the women enjoy better lives in their new situation than they did at home. But as the story continues, a sense of solidarity builds, and revelations of the power imbued by their position in the home become increasingly apparent. The story ends in a precarious place, and bids readers to consider their own approaches in standing up for themselves, as well as how easy it would be to take advantage of the trust built in any and all of their relationships.

Both of the aforementioned tales, and others in this collection, end in places ripe for further investigation, their revelations seeming almost better-suited to the midpoint, clearing the way for endings where more decisive action is taken and the consequences of that action laid bare. However, most of the stories in this collection end quietly, with characters hanging in the balance in ways that might leave you languishing on the edge of your seat.

Throughout, communities are formed and their strength tested by disruption. A standout of the collection is the story “Such Great Height and Consequence” in which a statue of a Confederate general is removed from its plinth. In its place, the town’s residents take turns occupying the pedestal. While at the start, the statue’s space is often occupied by the more privileged members of town espousing their fractious political views, the time slots come to be taken by people of all sorts with varied purposes—practicing wedding speeches, leading impromptu exercise classes, preaching, chastising other members of town for their table manners, doing crossword puzzles, painting, napping, etc. By giving so many characters space on the page for even the silliest activities, Norris demonstrates the validity of every person in our world occupying space in their own way. Although singled out by being present atop a literal pedestal, no one person’s chosen pursuit is treated as more or less worthy than that of their neighbors. The story also includes footnotes that inject even more wry humor into an already clever premise.

Another highlight of the collection, “Air Shifts,” follows radio personalities Jack, Bubba, and Tabitha. Jack and Bubba host a call-in show with sound effects and goofy anecdotes where they give advice to callers, but mostly in the interest of comedy. Tabitha’s show is far more saccharine—with “honey” and “I love you” flying this way and that alongside every generic platitude you can think of. As the story wears on, the cracks in these performances not only start to show, but widen and deepen. The truths the three have worked hard to shield from their audiences seem to be forcing their way out bit by bit. The callers are, of course, unsettled by these glimpses into their faves’ real lives, and as a reader, you may well be, too, as you try to guess exactly how much their facades will crumble by the end. While the story does occasionally take an interesting look at parasocial relationships, its focus rests more heavily on what the performer fails to keep private, and which aspects of authenticity their audience is or is not comfortable being exposed to.

While the most poignant tales in this collection include elements of humor that contrast pleasingly with their sober themes, every story presents thought-provoking questions about what makes a community hold strong and, conversely, what causes its individual members to break. Read, and find your own tipping point.

FICTION

by Kelsey Norris

Scribner Book Company

Published on October 17, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link