[ad_1]

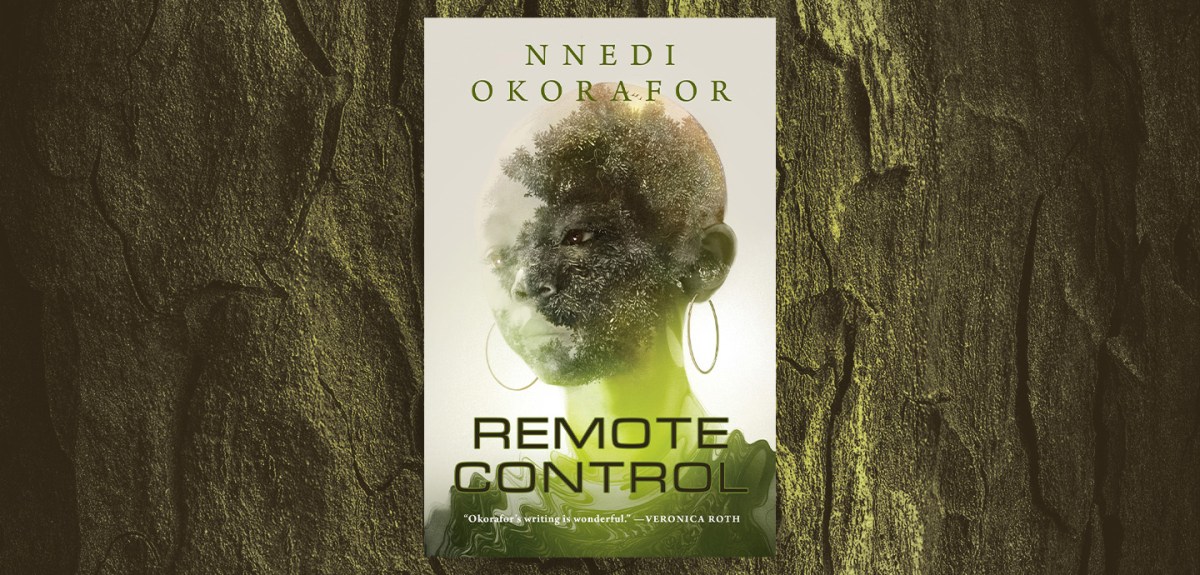

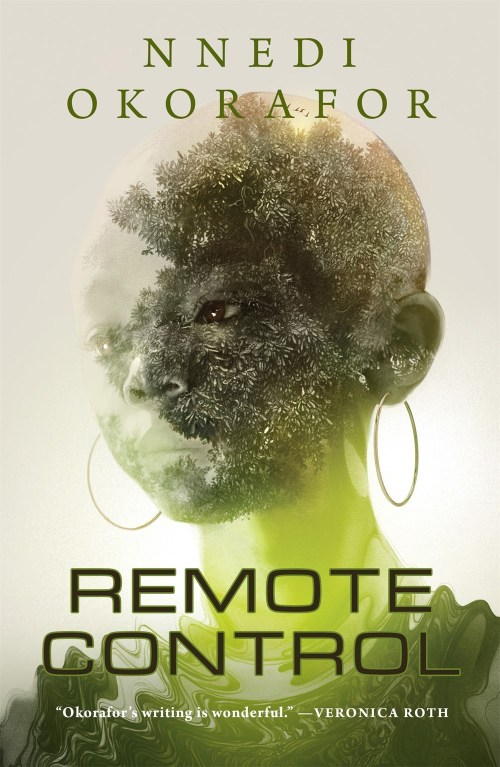

Sankofa is the adopted daughter of Death. With a glowing green light that comes from within her, she can take the lives of those around her. Nnedi Okorafor’s newest novella, Remote Control, introduces Sankofa through the stories many people tell about her—she is Death’s own remote control, they say. When she touches technology, it instantly breaks. A mysterious fox follows her everywhere she goes. There are many legends about Sankofa’s power, some truer than others, but no one knows the whole truth—not even Sankofa herself.

It all stems from a seed, fallen from the sky and found in Sankofa’s backyard. Before she was Sankofa, she was Fatima, a girl living happily on a shea tree farm in the Ghanaian town of Wulugu with her family. Her only hardship was malaria, and Okorafor builds her protagonist’s character amidst this adversity gently, as a little girl’s acceptance of the only version of the world that she knows. From the start, Fatima carried a burden within her body and yet lived resiliently.

Normalcy and the supernatural exist side by side throughout Remote Control, beginning when Fatima sees bright green meteors shooting down into nearby trees from her backyard. It’s not long after this that under her own beloved tree, a seed makes itself known to her, rising from the dirt in a wooden box. It is directly likened to Sankofa’s beginnings, “like a tiny Sankofa bird egg or…seed. It glowed a bright green like a star.”

This moment marks Sankofa’s origin story, the first inkling of the new version of herself that Fatima will be forced to grow into. Fatima’s powers aren’t long to appear—the green light glows from within her, usually to defend her from small creatures like a biting mosquito or stinging wasp. But Fatima does not understand why it happens or what it can do.

At least, not until a deadly accident in town sends Fatima flying. A car crashes into her, and when she lands in the street, the world around Fatima transforms to reflect the change in herself: “A corona of green sickly light burst from her, growing huge as it traveled from her small body. A bird dropped from the sky. A drone fell beside her.” When she wakes up, everyone in Wulugu—the people in the road, friends, strangers, her family—is dead. To mark the finality of this change, amidst the pain and shock, Fatima’s name leaves her mind forever. “It left her as a butterfly leaves a flower. She felt it go.”

This sudden and permanent shift is like that of so many superheroes familiar to Western readers—when Clark Kent becomes Superman, for instance—and reminds Sankofa of the book of myths she treasures. As she considers her new identity, she remembers “an image of Shango in her mythology book. She’d always liked this picture because he looked like a superhero, but was not.”

Sankofa, too, endures a transformation that might make her seem like a superhero, but she definitively is not. She recognizes the humanity in her mythological heroes, and she holds the same humanity in herself as she changes. She may possess an ability to take others’ lives, but above all, she is a young girl in search of home.

We see kindness guide Sankofa through her predicament. As she wanders from town to town, people fear that Sankofa intentionally comes to take people’s lives. But in reality, she only uses her power when she is asked to help the suffering or already dying, or if people threaten her own life. Once, Sankofa “had to kill another man who first tried to take her satchel of things and then tried to drag her into an alley. Some people may have seen it happen because the next day, strangers started giving her things.” The violence is a side effect, but still necessarily contributes to her mythos.

Sankofa exists apart from the mythology that is built around her by the people who live in the villages and towns she passes through. And as the reader is privy to Sankofa’s humanity, they are also let in to the greater truth hidden from average citizens but of which Sankofa becomes gradually aware. The quiet presence of LifeGen, an American corporation, is the hidden driving force of the novella.

When Sankofa was still Fatima, her seed was taken from her, sold to a politician who spoke in turn of selling it to LifeGen. Only Sankofa knows what drives her, and it is her missing seed. Sankofa has a sense of moral truth, a strong moral compass, that allows her to see the peripheral conspiracy of LifeGen as it deteriorates life and safety in Ghana.

The sense of something being amiss in the world appears repeatedly to Sankofa as she walks from town to town in search of her seed, meeting kind people as well as those who would oppose them for the sake of greed. Okorafor builds a deep awareness for the reader of what justice actually looks like, who is able to deliver it, and how.

Sankofa does her best to be just, but this foreign power and the world around her prevent her from being perfect. Lives are inevitably lost along the way. Sankofa is barred from justice for herself in many ways as well, even though other people demand it of her. She is a mythic figure yet she is entirely imperfect. She struggles to control the power she’s been saddled with just as much as she struggles to live, to grow up, to have a home.

The complicated nature of justice and the struggle to use her power for the greatest possible good carry Sankofa far from home and back again. An incredible Afrofuturistic legend, Remote Control offers a heroine who, when given power over life itself, relies distinctly on her humanity.

FICTION

Remote Control

By Nnedi Okorafor

Tordotcom

Published January 19, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link