[ad_1]

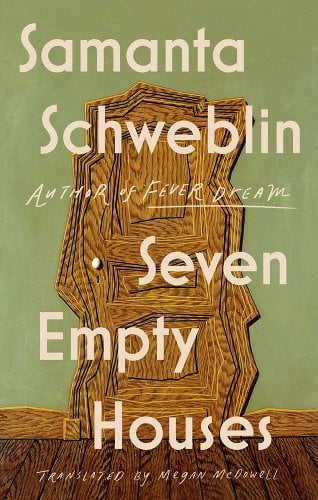

Each of the seven stories in Samanta Schweblin’s collection Seven Empty Houses engages with the subject of significant absence in ways that are distinct, while fitting easily beneath the same thematic umbrella. Characters search for missing people, objects, and pieces of themselves. Certain losses documented in these stories can never be recouped, yet each character achieves success in the form of lessons learned and newly established personal philosophies that they will surely carry beyond the final sentence of their tale. Although not as eerie as Schweblin’s readers might expect, there is certainly a great deal to linger over after the final page is turned. Chief among them, a choice: which of the losses bearing down on us are we willing to release to find relief?

The eponymous houses in these stories have often been emptied of something significant—literally and figuratively—before each story begins. Marriages have either ended in divorce or soured slowly over time; parents are abandoned and their children forced to pick up the pieces; loved ones have passed away. Each loss amounts to a rotting beam in the structure of a character’s life. In this book, Schweblin chronicles absences of a great and small variety: from underwear to memory to sense of self.

The story that veers closest to creepy is “An Unlucky Man.” At the start, the eight-year-old protagonist watches as her baby sister drinks a cup of bleach, unprompted. The very first line of the story decries her sister’s need to “be the center of attention,” and it is that need that allows the story to unfold as it does. The parents, understandably frightened, immediately sweep the family into the car and onto the road to the hospital. When traffic stalls, the protagonist’s parents demand that she remove her white underwear so her father can wave it out of the window to signal an emergency. At the hospital, the protagonist is told to stay in the waiting room while her parents talk to the doctors about her baby sister. As she waits, an adult man sits beside her and offers her a coupon for ice cream that he tells her he won. She refuses because she has been told not to talk to strangers. Is your stomach already turning? Well hold that thought, because when the man seems to understand her resentment of the situation her sister has caused, in a way that the prepubescent protagonist has heretofore been unable to articulate herself, she begins to trust him. What follows is an impressive high-wire act. Schweblin keeps “creepy” firmly on the table, but never fully takes us there. Nothing in this story is straightforward, which likely flies directly in the face of most readers’ preconceived notions of such a setup. The thing Schweblin does so expertly in the strongest of Houses’ narratives is not only making note of the assumptions her readers carry with them, but wielding them for her own, unforeseen ends.

Among the most intriguing examples of loss in this collection captures the fragile moment of understanding between two people who both crave a reprieve from the tension plaguing their respective romantic partnerships. This loss occurs in the final story, “Out,” in which a woman leaves her apartment sporting a bathrobe, with a towel coiled about her still-wet hair. She leaves because she cannot bring herself to say what she needs to say to her husband, opting instead to step away from the situation entirely. On the elevator, she meets a self-proclaimed “escapist”—a man who fixes fire escapes. He mentions that his wife “is going to kill him” because he still hasn’t made it home. The two part ways in the lobby, but reconnect outside on the street as the protagonist begins to wander. The man offers her a slow ride down the street to enjoy the night, as well as to avoid the eventual ire of his wife. The woman gets in, pleasant conversation ensues, and she considers telling the man about her sister, an intimate detail of her life meant to cement the bond between two people temporarily escaping their private realities. But before she can, real life intrudes in the form of a third party—a man running a kiosk—whose silent speculation over the two escapists irreparably ruins the delicate balance of their “game” (as the protagonist calls it).

Schweblin interrogates the concept of empty space by forcing it to take a different shape in every story. Although family sometimes creates and even embodies absence, they can also replenish what has been lost. Often, as Schweblin illustrates, they do both. In “My Parents and My Children,” the protagonist gets a front row seat to his ex-wife’s new life with a new man, a life that seemingly negates his use and very existence in not only the lives of his children, but within the memories in which he once played an essential role. In this instance, it is the one removed who appears to feel the weight of grief most strongly. However, when both his parents and children disappear, forcing his ex-wife into a parallel experience of loss, the protagonist’s presence is validated and the absence filled, if only temporarily. Another tale that foregrounds the parent-child relationship in its examination of the ways an empty space might be filled is the first, entitled “None of That.” In this story, a daughter comes to understand her mother’s impulse to look at, rearrange, and even steal from the beautiful homes she can never live in, hoping to regain some semblance of control in light of what fate has already seen fit to take from her.

The literal centerpiece of this collection is “Breath from the Depths,” a novella about an elderly woman named Lola whose greatest wish is to die. She is forced to rely on her husband to buy groceries and to take care of any other task that necessitates leaving the house. She keeps a list to help her remember the important things, among which is the item “If he meddles, ignore him.” The picture Lola paints of her life is one in which everyone around her is an intruder. Her doctor and her husband treat her like an invalid. Both, in her view, are foolish. Her new neighbors, a mother and son, are suspicious to Lola because of an implied class difference, or at least the difference between how Lola views them versus how she views herself. Slowly, the truth—that Lola is nowhere near as on top of things as she would like to believe—is revealed by the creation of yet another empty space in her life. In this tale, as in every other, Schweblin uses the negative space characters doggedly haul upon their backs, like snail shells they can shrink into, to bring their authentic selves into focus. Sometimes these unearthed truths are a welcome repellent against the distortions a character has allowed to warp their own perception; other times, the truth is an unwelcome alarm bell that shatters the illusion a person’s ego has created and held up to the rest of the world like a shield.

With Seven Empty Houses, Samanta Schweblin urges us to confront the emotions, ideas, and personal qualities we would dearly love to ignore, or to erase outright. Willful ignorance, Schweblin argues, is no kind of solution. Certainly, not one of any permanence. “If you gaze into the abyss,” Nietzsche warned, “the abyss gazes also into you.” In the houses Schweblin constructs, the empty abyss not only returns your gaze, but speaks its secrets aloud. How much longer will you keep your ears covered?

FICTION

Seven Empty Houses

By Samanta Schweblin

Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell

Riverhead Books

Published October 18, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link