[ad_1]

Brandon Taylor’s new novel, The Late Americans, begins with a character you wouldn’t want to be stuck with in your MFA workshop. Seamus is the only white male student in his graduate poetry seminar, where he doesn’t think anyone’s work is any good, since it’s all tied up in their individual traumas and not grounded in what he believes transforms writing into art. He doesn’t, for the record, think his work is good either, or else he doesn’t think it matters on the grander scale. Nevertheless, he doles out his cynical assessment of everyone’s work weekly until all but his friend Oliver are mad at him and their professor dismisses class for the day.

It’s not that his classmates’ pain isn’t real or that Seamus’s life is any better or worse than theirs, but “that they all had the same pain, the same hurt, and he didn’t think anyone should go around pretending it was something more than it was: the routine operation of the universe. Small, common things—hurt feelings, cruel parents, strange and wearisome troubles.” Rather than dare to disturb this universe with their personal writing, Seamus finds it easier to imagine they’re being watched by “some enormous and indifferent God prying the house open and squinting at them as they went about their lives on their circuits like little automatons in an exhibit called The Late Americans.”

The novel is Taylor’s third book to center around the lives of students at a Midwestern college. Each chapter turns the lens on a rotating cast of characters, most of them queer young men (with two women sprinkled in late in the novel), each with their hurts and hang-ups as they fight to carve out a space for themselves in the world, or else decide if it’s worth it to do so. Their arguments reveal how racial and class markers have shaped their perspectives, even as they share the common ground of a college experience: “they had all come to this speck of a city in the middle of a middle state in order to study art, to hone themselves and their ideas like perfect, terrifying weapons, and in the monastic kind of deprivation they found here, they turned to one another. Every dying species sought its own kind of comfort.”

There’s a sense that as they prepare for “real life”—like the title of Taylor’s first novel—they’re arriving too late to a dying nation on a dying planet, and their personal aspirations begin to feel worse than futile. Such dread causes the characters to act or speak cruelly, taking out their feelings of worthlessness on one another: “Everything they did was a posture, defensive or offensive, meant to demonstrate something to the outside world, perhaps that they were worthy or good or all right, perhaps to imply that they were in on the joke, that they were nothing and all they had were these crude choreographies of the self.” They want purpose or money, both if possible, but underneath their projections of self and future they want most to be seen by each other, to feel known, even once.

In an argument between Fyodor and Timo, two on-again-off-again lovers, Timo takes issue with his perceived cruelty of Fyodor’s work as a butcher, which Fyodor does because he needs money, remarking that Timo doesn’t understand what that’s like. After a shooting in Fyodor’s Alabaman hometown rattles him, Timo remarks that the shooter should be executed. When Fyodor points out the double standard Timo applies to animals and people, he recognizes the cruelty behind Timo’s logic and reaches for a broader, more difficult humanity. “They were nothing,” Fyodor understands, an echo repeated throughout the book: not just the shooter but Timo, himself, and everyone. “But they had in them the dignity of life, a right to be.”

It’s hard enough for the characters to extend such grace to themselves, let alone offer it to one another. Yet it seems to be part of Taylor’s greater project in this book, his first to put an unlikeable white character like Seamus front if not entirely center. When Seamus finally submits a poem to his workshop, one of his classmates remarks, “I mean, the white male speaker of the poem is not sympathetic, and maybe that’s what it’s trying to do? I guess? Bend our sympathies?” Throughout The Late Americans, Taylor does just that, rotating through a kaleidoscope of characters who may not earn your sympathies but deserve them nonetheless. It’s an artful novel of human hurt, and every character has dignity despite what they may believe about themselves and project onto others.

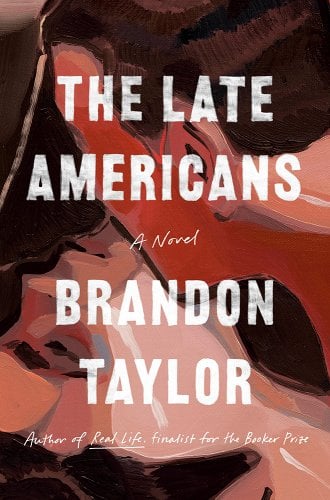

FICTION

The Late Americans

By Brandon Taylor

Riverhead Books

Published May 23, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link