[ad_1]

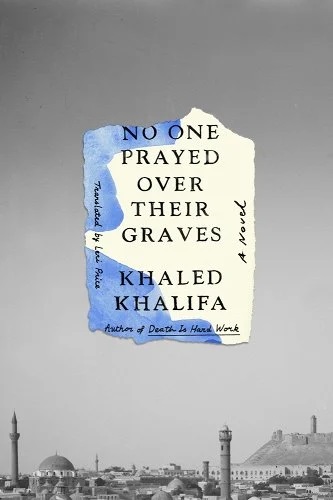

In 1907, an unrelenting rainstorm hit the fictional town of Hosh Hanna, triggering a massive flood that swept through its streets. The flood took everything with it: houses collapsed, livestock died, and all but two people, who desperately clung to a walnut tree, drowned. The story of the flood that swallows this small Syrian town outside Aleppo opens Khaled Khalifa’s latest novel, No One Prayed Over Their Graves, translated from the Arabic by Leri Price. But the flood is just one of many currents that wash through the area, and the others—the twilight days of a decaying empire, budding nationalisms, liberalism, and the grip of religious fervor, to name a few—claim just as many lives over the course of the novel.

When the flood hits, Hanna and Zakariya, two lifelong friends, are saved by their hedonism. Just outside Hosh Hanna, they had constructed a citadel dedicated to the art of pleasure, by which they had defined their lives. The aims of the citadel were ambitious. It fused a brothel, gambling den, and luxury hotel; the finest silks, wines, and foods flowed in from around the world, outpaced only by the women invited from other brothels throughout the region to sing, dance, and spend nights with its patrons. Hanna and Zakariya were at the citadel at the time of the flood. They returned from a drunken rave to see that their town and its inhabitants, including Hanna’s wife and child, had perished.

After the opening flood, Khalifa pivots to telling Hanna’s life story. Interwoven with the stories of Zakariya, their close friends, their family, and Aleppo itself, Hanna’s narrative stretches from before the flood in the late nineteenth century to the end of his life in the mid-twentieth century. The lives of the characters are dictated by the many pulses of Aleppo, a multipolar, cosmopolitan city under Ottoman rule, home to Muslims, Jews, and Christians, with delicate customs governing its culture. It is within this city that the onset of the twentieth century and the spirit of modernity it engenders clash with the slow, painful death of the Ottoman Empire and its attempts to maintain control. Khalifa’s story, like the era itself, is a battle between memory and the march of time. It unfolds in the aspirations of everyday people, as dreams are crushed, lives are lost, and power is negotiated in the midst of social, spiritual, and political turbulence. While the flood transforms Hanna from a libertine spirit pursuing pleasure to an ascetic meditating on the nature of life, it becomes clear that even if the flood had never hit, the upheaval caused by changing attitudes and customs would have made his past life impossible to continue. Natural disaster is juxtaposed with social disorder, hinting that it may be possible to recover from a flood, but there is no recovery from a ruptured social fabric; one can only renegotiate life anew.

Meditations on death—of people, selves, cities—permeate the novel. Sometimes death hovers above the characters; other times it is sought after and spoken about like a dear friend gone missing; and at other times it is simply a reality—the only ultimate, everlasting reality to which the characters resign. But just as death colors the novel, so, too, does love, in all of its forms. The characters’ lives are steeped in carnal love and desire, the transcendent self-sacrificial bond of lovers akin to Layli and Majnun, and love as a force worth dying for in order to honor one’s beloved. It is only these two realities—love and death—that survive the onslaught of time, persisting in every milieu. Old loves’ embers never fade, and the shadow of death never fails to cast life in stark contrast. The characters’ grapplings with love, death, and change are intimate, rendered in sensitive and piercing prose, evoking emotions that linger in the atmosphere of the novel.

Khalifa’s is a novel of sentiments and ideas brought to life in a vivid, dynamic Aleppo. The characters, city, and plot are vessels for meditations about the heaviness of time in an era of transformation, unfulfilled loves and expectations, and the inevitability of death in all of its glory. But at times, the construction of the novel itself can be a hurdle to clear to access its strengths. While Hanna’s life anchors the narrative, other characters enter and exit with ease, sometimes absent for long stretches of time before Khalifa reintroduces them in new contexts, offering small vignettes—interludes of sorts—of the plights of their lives, before they eventually weave back into Hanna’s life. Major events like plagues, famine, war, and genocide bubble up in the background, unexplained and briefly commented upon, and can feel underdeveloped without prior knowledge of the region’s history at this moment in time. Nonetheless, there is something to savor and ponder on each page, whether rich portrayals of Aleppo or heartfelt meditations, so patience with the novel will yield the best reading experience.

The essence of the book is best captured by two lovers, Aisha Mufti and William Eisa, whose lives unfold towards the middle of the story. Aisha is a woman of the times, fully embracing the new century and its possibilities, advocating for women’s education and advancement. William, a romantic painter, worked as a supervisor in a company owned by Aisha’s father, before quitting to pursue his passion for painting full-time. Aisha and William meet, fall into a deep, blazing love, and are willing to sacrifice anything in their path towards actualizing their love in marriage. Their love story comes to a tragic ending, though, when they are both killed while pursuing a life together, and their death haunts the rest of the book, both as symbol and as reality. Under different circumstances, they would have lived a joyous life together, and their mythical love would have been celebrated by the city. But, trapped in a storm of social change and political instability, they become martyrs of love and are buried together in seclusion. No one prays over their graves.

FICTION

No One Prayed Over Their Graves

By Khaled Khalifa

Translated from the Arabic by Leri Price

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published July 18, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link