[ad_1]

The work of Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Steven Millhauser demands to be read seriously since, at its often disarming core, it is about serious matters: time, memory, seeing the world as it is (reminiscent of Wallace Stevens’s “One must have a mind of winter to regard / the frost…”), the painful, inevitable divisions between human beings, the mindset of a suburban town’s chilling retreat into itself. My ordering of Millhauser’s preoccupations is not arbitrary; it is the pattern of his fiction. One notices the themes well before grasping the intentions, as opposed to the other, more typical way around. It could even be argued that his stories, as opposed to the passion play (I’m thinking of an immediately opposite sort of writer, say, D.H. Lawrence), are philosophical thought-experiments, trolley problems writ large.

In a 2011 interview with the French journal, Transatlantica, Millhauser confessed that the idea of ‘disruption’ is at “the center” of much of his work: in his words, “the sudden emergence of strangeness from the ordinary.” But Millhauser is no moralist. His new collection of stories, entitled—perhaps, at last—Disruptions, proffers no key to heaven’s kingdom. Simply but powerfully, it holds out only the promise of more worlds and yet more worlds for us to inhabit and ponder over, far from ordinary, and not all that far removed.

Arguably, all writers of fiction are makers of worlds, even the most painstaking realists. Millhauser’s worlds—akin to the micro-verse of Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, with its comically excruciating level of footnoted detail (for example, a disquisition on the obsolescence of Prell shampoo); reminiscent of Kafka’s castled jurisdictions of dread and nightmarish destiny; even of sly Nabokov’s transcendent puzzle-realms—may be seen as dimly reflective funhouse mirrors. They echo the shadowy play of our own world-in-motion, its evanescence and sad ungraspability. Disruptions, with its two novellas and sixteen short stories, is a dollhouse world-in-miniature: sometimes creepy, yet proudly displaying its own uniqueness, its all-encompassing itself-ness, reading like a report from an alternate world; though fully recognizable and, indeed, relatable.

A truly bravura story titled “The Little People” exemplifies this. A spin on Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and its unforgettable Lilliputians (Millhauser often weaves allusive tapestries), the tale is told not from a first-or third-person singular point of view but from the plural: the narrator, divisively, refers to ‘we,’ the people populating his or her town, as separate from ‘them.’ This Greek choral approach can be found in much of Millhauser’s fiction: one voice speaks for the town’s ills, as if a masked stranger breaks apart from a group of elders and, standing on the lip of the orchestra, relates to the audience his tragedy of Oedipus. Instead of a single protagonist, this story focuses on the town as a whole, as a multiple protagonist who must live side by side with beings in every way like human beings though only two inches tall, members of a self-governing community called Greenhaven. The pleasure, and this must be emphasized, the pleasure in reading a Millhauser story like this one is in its attention to detail, how lovingly the town and its successes and difficulties are crafted without the architecture of plot. (There are individual stories told about members of the little people working for, even falling in love with, the taller “white and middle class” folk, but there is no overarching narrative with central characters.) What we get instead, in a tone of Shirley Jackson-like objectivity that makes the bizarre seem mundane, is this:

Greenhaven women, in search of secondary incomes, advertise online an array of housecleaning skills, such as removing undetected particles of dust on mantelpieces, candlesticks, door handles, vases […] To watch a group of three housecleaners with their hair up in buns and their white aprons tied behind their backs as they push their meticulously crafted dust mops across tabletops or bend over with cloths the size of flies’ wings to remove dots of dust between the fringes of a throw rug is a pleasure and a revelation.

You can feel the delight Millhauser must have felt in writing this passage, as you also must admire the leap of imagination he had to make to plummet to this minuscule level of (un?)(quasi?) realistic detail, detail that cannot help but bring a smile to one’s own face. But, the key word here is “revelation.” This squinted seeing, the pushing aside of the everyday’s wide-lensed and overexposed in favor of the zoomed-in minute, reveals and restores us to the world, to the mystery of things ever before us but veiled by self-preoccupation. Case in point: a look inside the tiny homes of Greenhavenites via photographs taken by its residents, sent to ‘the big people’s’ computers and mobile devices. The little people live very much like humans do, but gradually the examining humans:

become aware of small differences, especially if we zoom in on the images. Then we notice details that were invisible before: the carved arabesques on window muntins, the painted rural scenes on the edges of bookshelves, the circus animals carved in cameo along the tops of baseboards in dens and playrooms. As we continue to enlarge, we discover new details within the details, such as wooden eighth notes carved along the sides of the vertical grooves of a piano leg, with an occasional mischievous face peeking out from behind a note. Many of us adopt in our own homes the hidden designs we discover in theirs, hiring experts from Greenhaven to bring about the desired effect. We admire the perfection of complex small objects like laptops or televisions that can rest on the tips of our fingers, but what fascinates us is the sense of an invisible world perpetually on the verge of becoming visible.

Many Millhauser’s stories make use of what he has called a guiding “motif” (though one could argue for a definition of symbolism) as in this case, “The Little People”’s concept of a town with a strange reality at its center, one it must come to grips with and ultimately be transformed by.

In “After the Beheading,” a twentieth-century suburban town’s employment of a guillotine engenders a fascination with the killing instrument that first empowers it, then diminishes it. In “Theater of Shadows,” a passion for shadows gradually metamorphoses the town into a community without the desire for light or color. In “The Summer of Ladders,” a town’s strange yen for ladders transports a man into the heavens, never to return. (See Nabokov’s “The Ballad of Longwood Glen.) In “The Circle of Punishment,” it is the more legal/philosophical notion of what punishment entails. In “Green” it is the greenery of bushes and shrubs. In “A Tired Town” it is, literally, a tired town.

This high concept dependence on “motif” to hold story together without the benefit—some might argue the necessity—of plot can at times be wearying. As in life, some concepts work better than others, though all of his tales have their especial delights, and, admittedly, one of the joys of being a reader of Millhauser’s work is seeing what kind of changes he can ring on yet another symbolist narrative. It is one of the hallmarks, perhaps the hallmark of his work, his structural obsession, rather like the obsession his characters display with the motif employed in one of their stories—the normal-sized people becoming more and more taken with the little people, for example—a meta-merry-go-round of totemic fixation: the writer’s psychology evident in the fiction, his created personages bouncing it right back at him, the reader moving through these doublings with a growing understanding not only of the importance of story-telling as a re-introducer, re-enlightener, to our many-spectacled world, but of our world itself as a ceaselessly traveling story, ever-changing, confounding only to the extent of its remaining obscure to an eye unwilling, untrained by art, to see.

FICTION

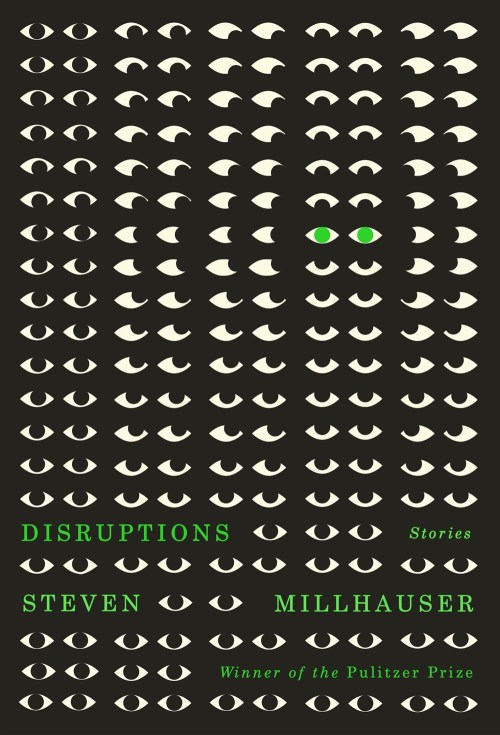

Disruptions

by Steven Millhauser

Knopf

Published August 1st, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link