[ad_1]

My neighborhood in Fort Worth, TX is undergoing rapid gentrification. It has gone from an industrial area where residents had to dodge tractor trailers to what’s now a commercial, entertainment district. The small, limited, public spaces have been made Instagrammable, and the neighborhood renamed to an easy hashtag. Where early residents lived in old, historic buildings converted to living spaces, “luxury” apartments and condos are being built on any available plots of land. I moved to the neighborhood at the fore of its transition—and, in a sense, helped pave the way for continued gentrification. But as I look around, it’s hard to imagine that the developers had long term residents (or any residents) in mind. Only a few of the business owners are local and live in the neighborhood, few residents of the “luxury” apartments will stay for more than two years. With each brewery, with the start of another apartment complex in place of a park, I keep asking the questions of who is all this for? And is it in any way contributing to the building of a community?

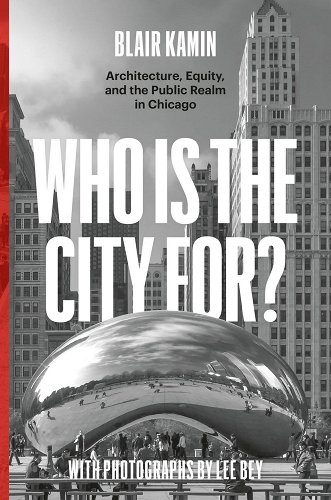

These are the questions Blair Kamin examines in his latest book Who Is the City For? For almost thirty years, Kamin was the architecture critic at the Chicago Tribune, and this book collects fifty-five of his columns written over the past decade. Kamin’s chief concern, through the lens of architecture, is that of equity and he sets up a guiding metaphor using the Millennium Park sculpture widely known as ‘the Bean.’ He notes how the sculpture’s metallic surface provides a striking reflection of the city’s growing and lavish downtown skyline, “But [it] does not reflect the reality of a very different Chicago.” For Kamin, ‘the Bean’ is a shiny object meant to distract from “weed-strewn vacant lots, empty storefronts, and unceasing gun violence” in a city like Chicago. Yet, how architecture can address equity isn’t limited to larger cities, playing an important role in more pastoral cities like Fort Worth, Indianapolis, or Columbus, Ohio. The essays in Who Is the City For? present Chicago as an analogue for any city and how architecture and urban design have an ability to bolster and transform the lives of individuals and their communities.

Who Is the City For? is organized into five parts. The first part takes on the idea of ego and uses former Presidents Trump and Obama’s Chicago architectural undertakings as examples of impact on the public realm. But most of the book revolves around the titular question and through what Kamin calls “activist criticism,” which is “based on the idea that architecture affects everyone and therefore should be understandable to everyone.” Coupled with Lee Bey’s striking photographs, Kamin effectively shows how architecture and urban design can reframe our lived environment and experiences.

Kamin takes on what he calls “plop architecture,” those new build “luxury” apartment/condo buildings stacked on top of, or butted-up against, parking garages. He writes about the structures’ failure beyond aesthetics: “the blank-walled garages weren’t just eyesores. They were energy wasters, encouraging people to drive instead of using bus and train lines that were steps away.” Kamin champions transit-oriented development, “which encourages construction of dense residential buildings near rail stops.” The thinking is that more people will live by public transportation, reducing driving, and therefore cutting energy consumption and pollution.

Kamin sees the world through the lens of architecture. Not just in a manner of what makes an attractive, successful building, structure, or park, but how architecture shapes more than the landscape of a city. Architecture is often overlooked—yes, we see buildings for their beauty or ugliness, note monuments and specific characteristics of something’s “architecture.” But we don’t see or understand the full impact of architecture on its surrounding environment, its ability to fight climate change and address poverty. Kamin is demanding action in Who Is the City For?. We take shared spaces for granted, but Kamin argues, “The public realm can serve as an equalizing force, a democratizing force. It can spread life’s pleasures and confer dignity, irrespective of a person’s race, income, creed, or gender.” He’s imploring us to do more than look, he’s showing us the power of seeing, examining, and how to ask the right questions.

NONFICTION

Who Is The City For?

By Blair Kamin

University of Chicago Press

Published November 21, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link