[ad_1]

When regarding works of art, Kandinsky asked the viewer, listener, reader to consider “[…] whether the work has enabled you to ‘walk about’ into a hitherto unknown world.” Before this request was an imperative: “Stop thinking!” This can be read as a rejection of searching for a deeper meaning, or engaging in excessive interpretation that destroys a piece of art leaving in its place a dense exegesis—which for critics (and we are all critics) can sometimes seem de rigueur. Maybe what Kandinsky’s words are imploring us to do is consider the “feel” of a thing rather than the “think” of it. To let art serve as an emotional catalyst through which we can see our own world in new ways. Art can be used to help us build containers in which we navigate our experiences and understand reality. It’s why we not only engage with someone else’s work, but also create our own: how do we make sense of a world when it so often makes no sense at all?

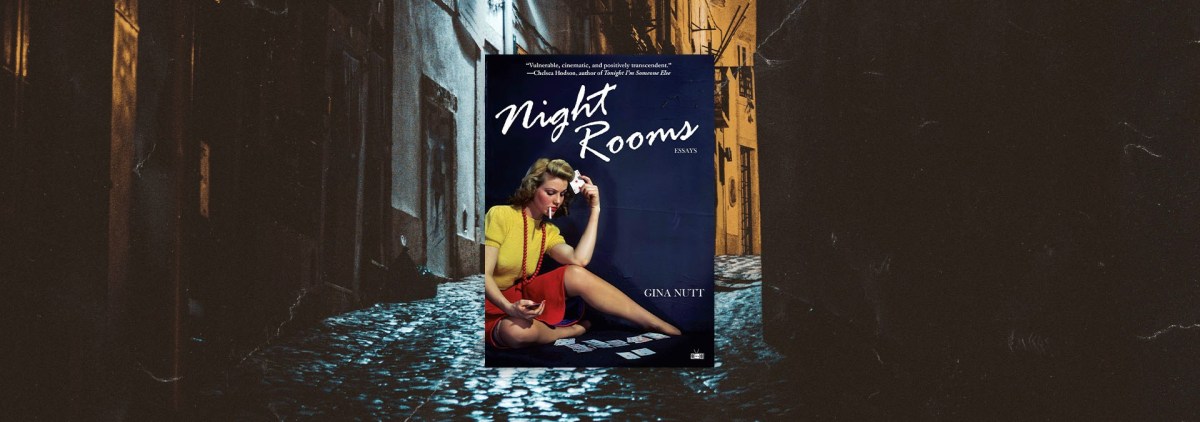

Maybe for Gina Nutt, the answer is to write about horror films. “If we attach ourselves to art,” she writes, “maybe art can attach itself to us.” A symbiotic relationship, a mutual, consensual using. In her collection of interrelated essays, Night Rooms, Nutt uses the films and common horror tropes to examine her own lived experience. Not all monsters have claws and fangs; not all scary things go bump in the night. The jump scares, bogeymen, and terrors hiding in the shadows are her gateway into writing about moments of trauma, grief, loss, and relationships. Horror can help us process. Grief studies have shown that trying to make someone feel better is going to make them feel worse. But a horror film can let us experience our pain along with the characters knowing they won’t all survive.

In an early essay about the suicide (a theme that is threaded throughout) of her father-in-law, Nutt uses a Joy Williams essay and the film Jaws as primary entryways to talking about his death. “A shark is a metaphor for an unexpected death, as well as immense feeling, the sense of being tugged beneath the water.” That feeling of something destructive looming, ready to attack. The ocean, too, in this essay becomes a metaphor for the unexpected death, the suicide, and perhaps depression. “The ocean is balm and horror. Think of the surface, not the plunge beneath, the depths. Think of starfish, seahorses, dolphins, and sea lions, not sharks, or deep-sea creatures.” What is hidden? What’s behind the smile, the laughs, the “Yeah, I’m okay”? She quotes Joy Williams, “Who among us knows the extent of the sea’s true abyss?”

Nutt is never explicit, never spells it out. Rather, she lets the images do the work. “That a shore exists—even if its line doesn’t cross the horizon—is not likely a comfort to someone swimming in the middle of the ocean.” It’s haunting and beautiful. And it makes me feel sad and alone, like that sadness and loneliness will never end. It’s a metaphor that makes me feel rather than parse.

The essays in Night Rooms don’t have titles, just numbers; they function more like chapters. They are fragmented, lyrical, full of white space for ideas and themes to echo through. They bleed into one another maintaining the same structure, rhythm, voice, and tone—this observation is not meant as a slight; Nutt is in full control of how form and content are playing together. As self-contained essays, they are ephemeral, in that their bleeding leads to a loose conglomerate—a container made of containers.

Night Rooms becomes the aforementioned container, constructed from artistic engagement with horror films and pop culture in which Nutt attempts to make sense of what’s around her. Sometimes we can’t look straight in the face of our reality. Instead, we need something to look through, something that refracts, gives us a new angle of vision that makes it just this side of bearable. Engaging with the scary on screen, like engaging with the scary in the world, takes courage. Facing trauma of any kind, even facing it at a slant, is an act of reclamation, agency, and power, as Nutt very well knows: “I am making a lineage of what lingers. I am trying not to be afraid anymore.”

NON-FICTION

Night Rooms

by Gina Nutt

Two Dollar Radio

Published March 23, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link