[ad_1]

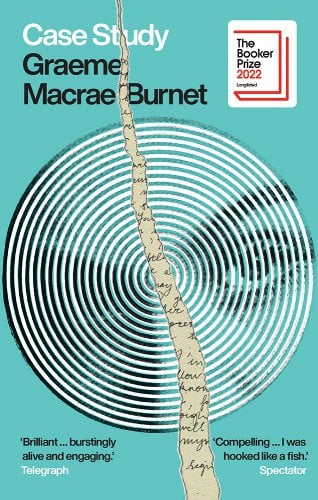

“Who is to say which is the original and which is the imposter?” queries Graeme Macrae Burnet in his 2022 Booker-Prize-nominated novel, Case Study. The question is applicable to a character in the novel, to documents reproduced within the novel and, most intriguing, to the author himself.

Burnet is the ultimate unreliable narrator, and Case Study serves as a worthy addition to his oeuvre; however, defining that oeuvre is a challenge.

His 2015 novel, His Bloody Project, brought his work to an international readership with its Booker-Prize shortlisting. Burnet researched His Bloody Project at the Highland Archive Centre in Inverness, Scotland; inspired by a prisoner’s 1869 memoir, Burnet presents articles, police and witness statements, post-mortem reports, and excerpts from a memoir by a man who interviewed Macrae (the prisoner’s patronym). Burnet invites readers to examine “discrepancies, contradictions and omissions” in the archival documents, but international readers depend exclusively on Burnet’s book to assemble an understanding of the crime.

His Bloody Project inserts itself into the tradition of Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace (1996) and Hannah Kent’s Burial Rites (2013). Such novels explore questions of interpretation via events in the historical record: central characters are accused of violent crimes against higher-status individuals, whose stories are prioritized because of their socio-economic privilege. In contrast, Burnet credibly presents documentation—all of which he has invented—with enough nuance and detail to position His Bloody Project as historical true crime.

But before all of that, Graeme Macrae Burnet’s name appeared on the 2014 novel The Disappearance of Adèle Bardeau, as the translator. In the foreword, Burnet marvels that Raymond Brunet’s cult classic hasn’t previously been translated into English; it’s been “almost continuously” in print since 1982 in France, buoyed by the subsequent film’s success. In the afterword, Burnet examines the alignment between various events and characters in Raymond Brunet’s novel and specific biographical details and prominent figures in the French author’s life. Burnet notes that Raymond Brunet died troubled and alone, having struggled to accept the film—“It was not a fictional character he was watching on screen, but a projection of himself.”

Raymond Brunet’s mother apparently outlived him, and after her death, a litigation firm dispatched an envelope containing a manuscript titled The Accident on the A35. Burnet’s foreword to this 2017 novel describes how amused and guilty the author’s solicitor felt, actually possessing the second manuscript after the author’s death, amidst rumors of its existence. Burnet’s afterword provides additional intersections between fact and fiction in Raymond Brunet’s second novel. “So the premise and central characters of the novel were clearly rooted in reality, but what of the narrative?” Burnet asks, before explaining how one of the novel’s plotlines is seemingly drawn from the life of the man who directed the film based on Raymond Brunet’s first novel.

In the first of these translations, Burnet’s supplementary material spirals around a quotation from Georges Simenon’s autobiographical novel Pedigree: “Everything is true while nothing is accurate.” In Burnet’s commentary on Raymond Brunet’s posthumously published work, he draws attention to this passage from Jean-Paul Sartre’s Words: “What I have just written is false. True. Neither true nor false.” It’s more important for all of this to be believable than for it to be true, and Burnet creates a framework in which readers can believe, using his “expertise” on an imagined novelist (Raymond Brunet) to increase readers’ trust in Burnet. Despite positioning this duology in reality, however, Raymond Brunet is a fictional author.

But what of the author’s responsibility? In His Bloody Project’s “Historical Notes,” Burnet indicates “any inaccuracies, whether by design or error, are entirely my own responsibility”. In Case Study’s acknowledgements, Burnet accepts responsibility for a portion of the work, but “any inaccuracies” from the excerpted notebooks are that author’s responsibility. As Burnet’s fictions increase in complexity, he appears to distance himself further from his creative work.

In Case Study, Burnet presents two additional authors, whose documents are made available to readers. Most compelling are the private notebooks of a woman who is preoccupied by a young woman’s suicide; she believes that she has recognised the dead woman in a psychotherapist’s published work, despite that author’s having concealed the woman’s true identity. The author of the notebooks presents evidence of the psychotherapist’s misconduct and excerpts his publications; this complex structure allows questions about selfhood and identity, confusion and delusion, to proliferate.

Case Study is not a unique narrative; novels as diverse as Jesse Ball’s Silence Once Begun, Mohsin Hamid’s Moth Smoke, and Kwon Yeo-Sun’s Lemon (translated by Janet Hong) require that readers construct their own understandings, based on incomplete or conflicting accounts, of tragic events.Graeme Macrae Burnet stands apart, however. He not only presents different iterations of narratives, but different versions of authorship. Like a character in Case Study, Burnet has “a flexible relationship with the truth.” In translation? Not one word he writes is true.

FICTION

Case Study

By Graeme Macrae Burnet

Biblioasis

Published on November 1, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link