[ad_1]

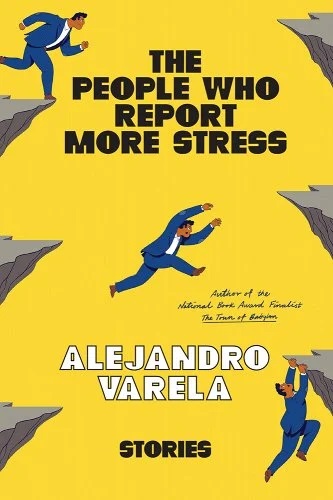

When I’m excited about a book I skip the back cover blurb and jump right in. Why would I need to read a description of National Book Award finalist Alejandro Varela’s new story collection, The People Who Report More Stress, when I already know how much I love his work? And short stories by design are meant to be read without context. You dive in and learn everything about the characters and circumstances as the author intends for this information to unfold. But, in this case, immediately diving in meant I missed the description that the stories are interconnected—something I didn’t realize until nearly halfway through the book.

I’m admitting to this faux pas because it speaks to the thematic cohesiveness of the collection and the range of these stories. (I also didn’t want to assume that because most of the stories’ protagonists shared characteristics of being male, queer, and Latinx, they must be the same person.) But the narrative range is notable—differences in points of view (stories are told through first-, second-, and third-person POVs), but also the stories themselves are quite distinct. The protagonist in the opening story, “An Other Man,” has the blessing of his husband to seek an extramarital lover. In the next, “She and Her Kid and Me and Mine,” we meet the protagonist having to host a playdate with his son’s white friend and their outwardly polite yet secretly prejudiced mother. And we meet Eduardo—the same protagonist, who I wasn’t sure was indeed the same character at this point in my reading—as a child through a story that centers his father, who works in a restaurant but begins selling high-end designer clothes to support his family. Because the circumstances from which we meet Eduardo vary so much, no two stories feel the same.

But regardless of whether the story deals with queer parenthood, a terrible cab ride, online dating, or watching an affluent Swedish couple’s children, under the surface of each story is the toll our society’s inequities take on the health and wellbeing of marginalized people. Perhaps no story so deftly reveals that as “The Six Times of Alan,” in which the narrator is back to see his white therapist, who is clueless and racially insensitive, if not completely incompetent, following a racist incident. The story acutely portrays the cyclical nature of the damage perpetuated by white supremacy: this protagonist seeks help to deal with the toxic stress of living in a society full of systemic and interpersonal racism, and yet the person who is supposed to be equipped to help has their own personal biases. A lot of great and important contemporary fiction dives into systemic and interpersonal racism—thankfully; it’s something that needs continuous and persistent examination to be dismantled—but what sets Varela’s work apart is the way it shows how the constant onslaught of abuses (borrowing Ibram X. Kendi’s preferred term over “microaggressions”) impacts individuals’ health. Like in Varela’s novel, The Town of Babylon, he manages to elevate these important issues without his work ever feeling didactic or forced. He does so by having characters who work in public health, so they’re naturally hyperaware of the effect the stress of interpersonal racism and class conflict can have. As the narrator in a different story puts it: “Humans regularly report behavior change in response to discrimination. I haven’t come across research on people who stop hailing cabs, but they do stop seeing doctors whose intentions they don’t trust. They stop going to parks where they no longer feel welcome. They stop applying for jobs they don’t believe they’ll get. Anything, it seems, to avoid unnecessary stress.”

But part of the magic of the stories in The People Who Report More Stress is they stretch beyond the thematic glue that holds the collection together. They examine long-term relationships, parenthood, communities, and class with humor and heart. They’re inventive and surprising. Another striking story is “Grand Openings,” which is modeled after Margaret Atwood’s “Happy Endings,” but only in form—Varela makes the repetition of alternate multiverses of Eduardo and Gus completely his own. And that’s why I tore through the collection without trying to orient myself first: Alejandro Varela is a singular voice, a brilliant fiction writer whose work is wholly original, managing to be both important and completely entertaining. I look forward to rereading this notable and necessary collection, knowing from page one the stories are interconnected—I’m certain further surprises await.

FICTION

The People Who Report More Stress: Stories

By Alejandro Varela

Astra House

Published April 4, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link