[ad_1]

I was first introduced to Kirstin Valdez Quade’s writing in a graduate workshop, when the professor led a discussion on the short story “Nemecia,” from her debut collection Night at the Fiestas. Since then, I return to this story whenever I reach the distinct point of writer’s block where I need to remind myself what good fiction looks like.

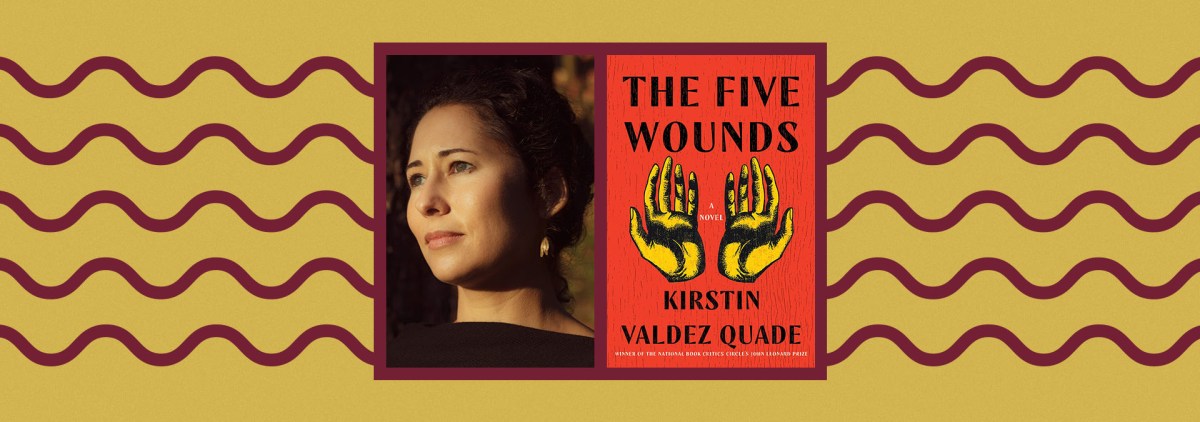

Quade’s work has a way of revealing itself in new ways with each read, as her characters are so complicated and memorable that they demand your attention and reflection. Originally appearing as a story in collection, The Five Wounds shares these trademarks of her short fiction with the scope and pull of an ambitious, generational novel. The Five Wounds follows middle-aged Amadeo, his estranged pregnant daughter Angel, and terminally-ill mother Yolanda, over a single year, as they struggle to redeem themselves by correcting previous missteps, cobble together a worthwhile future out of a broken past, and simply coexist under the same roof.

Kirstin Valdez Quade takes no half swings and refuses to write a character half-heartedly. Readers will love her characters for all their beauty and boils, and will find themselves captivated, frustrated, gutted, and hopeful for them as well. Weaving together painful personal and collective histories into this unforgettable family, The Five Wounds is just as likely to break your heart as it is to make you break out laughing. It’s a novel to place prominently on the corner of your writing desk or on your favorite bookshelf and return to whenever you want to remind yourself what an excellent novel can imprint upon you.

I spoke with Kirstin about expanding her short story into a novel, writing past empathy blocks, and the possibility for redemption in fiction.

Michael Welch

The Five Wounds began as a short story that was published in The New Yorker and later in your debut collection Night at the Fiestas. Can you talk a bit about how this story evolved into a novel? Was there anything particularly challenging or freeing about expanding the story’s scope?

Kirstin Valdez Quade

When I wrote the short story and when it was published, I thought it would be just that, and I moved on to other stories. A couple years later, an editor at W.W. Norton emailed me and asked if I’d ever considered turning it into a novel, and I wrote back and said, “no, it’s a short story and I’m working on other short stories.” I thought that I believed that, and then a little while after I was looking at drafts of some short stories that weren’t working. I knew that there were similarities, but they just weren’t working. And I realized that all three of these stories were dealing with basically the same family dynamic—a codependent mother, her grown son, and his estranged daughter—and these stories were all sort of taking different perspectives and they were different ages and they all had different names, but I hadn’t understood until that moment that these were actually Amadeo and Angel and Yolanda. So I thought, “oh gosh, maybe I do have a novel.” These characters still have a hold on me. So I decided I would devote that summer to seeing what I could do with it. I would try to expand it and see if it’d work. It was really fun to spend more time with the characters and in the points of view of those who were supporting characters.

I think one of the challenges was that the story was published and appeared in print twice, it felt permanent in a way. It took me a while to be able to break it open and take what I needed from the story and leave behind what I didn’t need. But when I was able to break it open then things really opened up for the novel.

Michael Welch

In the opening chapters we see that the character of Amadeo, who is playing the role of Jesus in his town’s annual reenactment of the Stations of the Cross, asks to be actually nailed to the cross. But in the original story, this serves as the final moment of epiphany for him. How did your perspective of this project change when you turned the conclusion into the inciting incident?

Kirstin Valdez Quade

I think when I was toying with the idea of expanding the story into a novel, one of the questions for me was “okay, so what happens the next morning?” He’s had this big epiphany, he sees his daughter suddenly with clearer eyes, but what happens the next day when he wakes up in his same bed in his mom’s house and his pregnant daughter is in the kitchen making scrambled eggs? Obviously as you pointed out, the end of the first chapter is too early in the arc of the novel for Amadeo to have an epiphany. But I think in life too, real character change rarely happens from a single epiphany. Sometimes we need epiphany after epiphany, as well as a lot of steady work to change.

The Penitentes is something that I find incredibly moving, because I think that the practice of physical penance always struck me as a really beautiful and empathetic form of worship that’s trying to not just witness the story of Christ’s suffering and death, but to actually involve oneself in it. And that always seemed really moving to me. Amadeo is a really enthusiastic participant in it but he misses the point. For him, it’s about performance. He wants so much to change that he wants to do the best, most realistic performance, which involves the nails—which is not a part of the traditional practice at all. This is Amadeo’s extreme and misguided take on it. So I wanted to know, where does he go from all of this if this doesn’t actually change his life. Is he able to change his life and become the father and person he wants to be?

Michael Welch

Within the single year when this novel takes place, we see the women in the Padilla family suffering at two very different stages in their life, with Angel experiencing postpartum depression and Yolanda coming to terms with her terminal cancer diagnosis. How did you see these two character arcs coming together and interacting as you wrote?

Kirstin Valdez Quade

Yolanda and Angel are both caretakers. Yolanda is obviously the matriarch of this family and is still cooking dinner and supporting her thirty-three-year-old son. And I think from a young age, Angel has been taking care of herself and her mother, and certainly once her child is born, that role of the caretaker takes on this new urgency for her. As Yolanda faces the end of her life, she turns inward and begins to take care of herself in a way that she hasn’t up until that point, and begins to really examine some important moments and losses in her own life. Angel, I think, is at the beginning of her caretaking journey, poor thing. But I think part of her arc too is demanding that the people who are supposed to look out for her actually start doing that. It’s interesting: until you posed the question I hadn’t quite seen those parallels as clearly, but toward the end of the novel they turn to and begin to take care of each other.

Michael Welch

I was really drawn to the moments where you let the outside world seep into this intimate novel. In particular, there’s a chapter where Yolanda reflects on the history of conquest in America and how it has carried into her family’s history. Can you talk about your approach in weaving this legacy of external violence into this family drama?

Kirstin Valdez Quade

I think those two histories are inseparable. Our family histories are a part of broader cultural histories, and broader cultural histories make their way into our families. There is this really painful history of conquest and reconquest that started with the Spanish arrival in the region of New Mexico. And over the centuries since, there have been economic conquests and the borders have shifted; there’s been so much change and so much pain there, and that history is still alive today. It’s palpable. And these discussions are happening today about how we revisit these narratives of our history, and how we come to terms with that legacy of violence and possession. So I think there’s no way for that kind of pain both suffered and inflicted to not make its way into the family.

Michael Welch

You perfectly capture something common in many families, which is the relative whom you have a unique, powerful love for despite the disappointment and hurt they continue to cause. For Amadeo, how did you strike that balance between building him up as a sympathetic character on his path toward redemption and having him choose selfishness over his family?

Kirstin Valdez Quade

Well, first off, I appreciate that you do find him sympathetic. I find him sympathetic, but he’s an incredibly flawed character. He’s a deadbeat father, he’s mooching off his mother, he has a history of domestic violence, and he’s self-involved and takes no responsibility for his choices in life. There’s a lot to judge him for, and that was a real challenge for me when I was first writing Amadeo. When I was working on this story, I had this empathetic block. I was judging him too much. It was so uncomfortable to fully embody his perspective, and the story suffered because of that. I was not allowing him to be fully human. It took a lot of drafts and revision to truly embody his point of view. What makes me care about him and root for him is that he wants to be a better person. From the very beginning, he’s trying to be better and change his life. He wants to be a better father and provider. And even though he fails for much of the novel, I’m rooting for him because he’s trying.

Michael Welch

It really is a fantastic trick that you pull off, because as a reader I do feel sympathy for him while at the same time understanding that he’s incredibly flawed. How do you approach breaking through that empathetic block, especially when you’re writing a really flawed or bad character?

Kirstin Valdez Quade

All of our characters have something that they’re hiding that they don’t want to reveal to the reader, which is often the source of the empathetic block. At least it was for Amadeo, because I couldn’t access that in the beginning. So this is really corny, and it’s a revision exercise I assign my students and do myself when I encounter this problem. I open a new document and write a conversation with a really belligerent therapist who is just trying to get at the heart of what the character is hiding or ashamed of or not able to acknowledge. And it was through that exercise and really just hammering away at him, asking “why did you abandon your daughter? Why, why, why?” I think maybe one line of that dialogue made it into the novel, and I couldn’t even tell you which line. Oftentimes none of the dialogue will make it in, but the knowledge does.

Michael Welch

The Five Wounds explores the theme of “becoming saved,” both saving oneself and others. As a writer, do you think all characters deserve redemption, or at least the chance at redemption?

Kirstin Valdez Quade

I do. I have a Grace Paley quote above my desk that says “Everyone real or invented deserves the open destiny of life.” That really guides me as I write. I want to offer all of my characters—even the ones who are on the periphery of the story—the possibility of change and of movement. That’s one of the things that I revise for. Am I allowing this character to be complicated and fully themselves? Am I using this character in service of the story I think I want to tell or in service of the other characters? What does this character actually want? And what would this story be if this character were telling it? You know, literary fiction is about character change, and that to me is just inherently hopeful. I like the idea that we can change, even if the change isn’t necessarily for the better or lasting. But I do believe that characters can change and should be given the chance. I think that about people too.

Michael Welch

Are you eyeing any other short stories from your debut collection to revisit and adapt?

Kirstin Valdez Quade

Oh, god no. I’m really glad I did this and wanted and needed to spend more time with these characters. I think my next novel is going to be something completely fresh and grows out of itself. And it’s going to be slender and one point of view. You know, not a large, multi-point of view, rational story. Although I’ve heard other writers say they were going to do that and then you know, 400 pages later they realized they fell right back into their old patterns.

FICTION

The Five Wounds

By Kirstin Valdez Quade

W.W. Norton & Company

Published March 30, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link