[ad_1]

Georges Seurat’s painting A Sunday on La Grande Jatte is a marquee visitor attraction at the Art Institute of Chicago. This painting of mid-19th century Parisians picnicking on the banks of the Seine is large, but the figures within it are made up of millions of tiny colored dots. To view the painting, visitors can stand back to see the bigger picture, or lean in close and examine the dots individually, as atoms of meaning, small but essential building blocks of the experience of the painting.

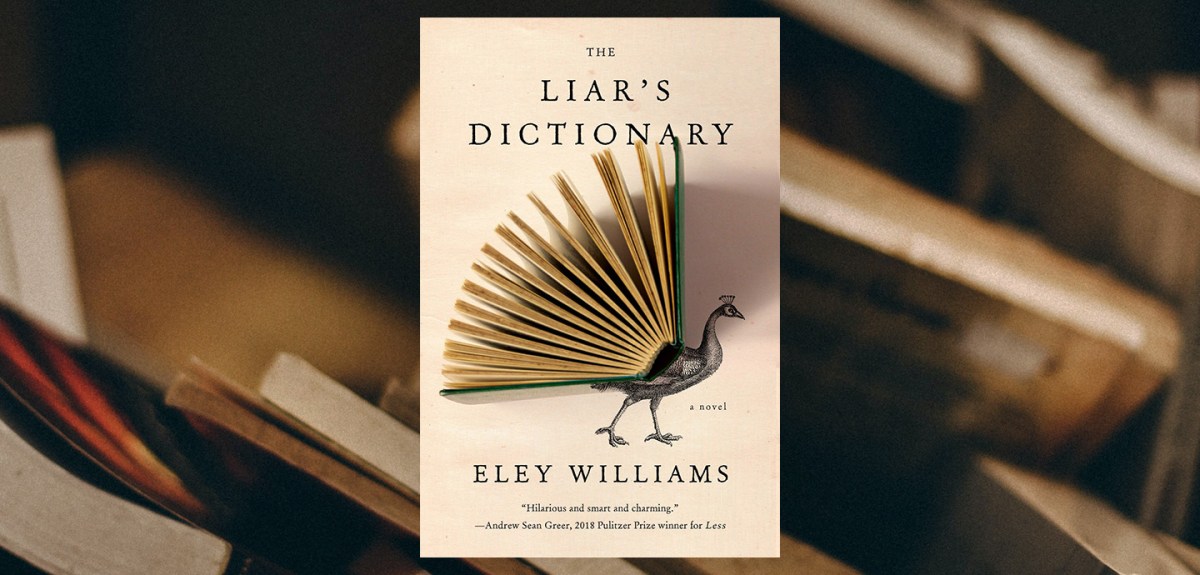

Eley Williams’s The Liar’s Dictionary also invites its readers to take a close look, but its subject is no Sunday picnic. Williams’s book is about language itself, and in it words are both the brush strokes and the bigger picture.

The Liar’s Dictionary is about the fictional Swansby’s New Encyclopaedic Dictionary, a 19th century reference volume that was intended to be the most comprehensive British dictionary ever created. But the project was disrupted when WWI drained its workforce and forced printing presses to be melted into munitions. It is abandoned, unfinished, and rather than fulfilling its founders’ vision of becoming the crown jewel of British lexicography, it is instead known as a “folly,” the “noble damp squib” of British dictionaries.

However, despite its embarrassing legacy, the Swansby New Encyclopaedic Dictionary lingers into the present. The latest in the ancestral Swansby line and current Editor-in-Chief David Swansby hires Mallory as an intern to assist him in his quixotic quest to update and digitize the dictionary (and rehabilitate the Swansby legacy). Tucked away in a dilapidated office in the now-historic Swansby House, Mallory is tasked with updating definitions, checking spelling and punctuation, and fielding terrifying daily phone calls from an anonymous person who tells her that she will burn in hell for working at a publication that changed its definition of marriage to a union between “two persons” rather than “a man and a woman.”

Back in 1899, Peter Winceworth also suffers through his days at the Swansby House. Winceworth is an introverted lexicographer who believes his job is pointless and feels disconnected from his colleagues and his life. Extremely socially awkward, he feigns a lisp and, though his grasp of language is magisterial, struggles to engage in basic conversation. When he reluctantly attends a birthday party for his odious but illustrious colleague Terence Frasham, he tries to conceal himself behind a plant to avoid socializing. He discovers that the space is already occupied by a woman who seems to share his outlook and sensibilities, and he falls in love with her immediately. Unfortunately, the woman happens to be Frasham’s new fiancée.

Though separated by more than a century, Winceworth and Mallory’s experiences in Swansby House are surprisingly parallel, and not just because they work in the same building on the same project. Mallory, a lesbian who is not out at work, experiences the same sense of alienation that haunts Winceworth. They both battle harassment on the job, whether from anonymous callers or from the jeering disrespect of colleagues like Frasham. They also both find language to be lacking in its ability to capture their experiences. And when Winceworth tries to remedy this, it causes chaos for Mallory even 100 years later.

The connections between Winceworth and Mallory are impressively detailed, and echo neatly back and forth one to another, effortlessly collapsing the decades between them. But these characters and their concerns are frequently overshadowed by the dynamic role that language itself plays in The Liar’s Dictionary.

Far from mere mechanisms of storytelling, Williams’s words constantly call attention to themselves. Throughout the novel, language romps and preens, serving as playful trickster and creeping villain, hapless blunderer and penetrating blade. The book’s baroque, self-referential writing style combines medium and message in a messy maelstrom that intrigues and occasionally overwhelms. Through this kaleidoscopic lens, Williams interrogates the charged nexus where language “meets” human experience—and the book’s humans’ experiences—and finds the connections there crucial, but faulty.

While the book’s incisive meditation on language can make its human characters seem a bit fuzzy in comparison, The Liar’s Dictionary is not solely cerebral. Its esoteric leanings are balanced throughout with humor ranging from wry to ridiculous. In the book’s preface, the author describes the debate over whether dictionaries should play a role in policing language:

“Whether a dictionary should register or fix the language is often toted as a qualifier. Register, as if words are like so many delinquent children herded together and counted in a room; fixed, as if only a certain number of children are allowed access to the room, and then the room is filled with cement.”

This kind of cleverness runs alongside a streak of Monty Python-esque humor, as when Winceworth passes the time at a party by pacing the room in the shape of the letters of the word “hello,” thereby looking busy enough to avoid conversation.

The Liar’s Dictionary may ultimately excite the intellect more than the heart. But as its characters struggle to free themselves from all artifice, even—or maybe especially—that of language, you may find yourself wanting to stand back to see the bigger picture, even as you lean in close to examine its dots.

Fiction

The Liar’s Dictionary

By Eley Williams

Doubleday Books

Published January 5, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link