[ad_1]

Myths about romantic and familial love run rampant in our heteronormative, patriarchal culture. As children, we’re trained to believe that romantic love is the most noble love of all, that breakups are failures, and that being a mother is the purest way to love a child. Queer and trans communities have been pushing back against these myths for generations. Lee Lai’s debut graphic novel, Stone Fruit, is a remarkable contribution to this chorus of queer storytelling. In this quiet work of startling complexity, she examines how these myths play out in the lives of three women — and joyfully refutes them. Instead of a staid world of expected boundaries, she draws the messy, confounding world that queer people actually live in. In this world, aunthood and motherhood hold different but equally profound meanings. Endings are possibilities. Sisterhood eases wounds romance can’t touch. Found family and family of origin are not always easily distinguishable.

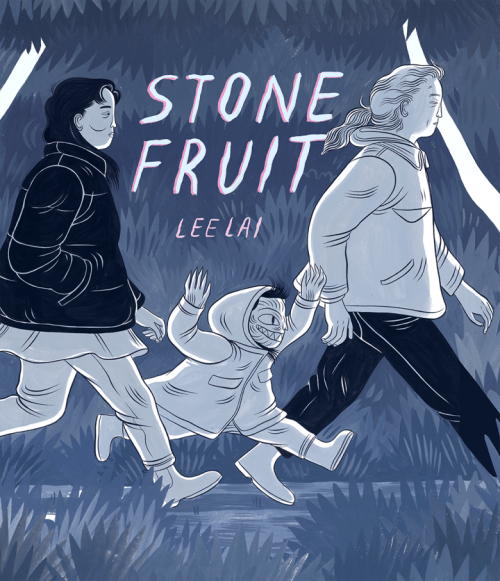

The book opens with a breathtaking series of panels that invites readers into the magical world that queer couple Ray and Bron have created with their six-year-old niece, Nessie. Ray, Bron, and Nessie are running through a park, singing, laughing, and chasing each other. But they do not appear as humans. Lai introduces us to these characters as beautiful monsters. They have huge mouths full of snapping teeth. Their long, loose limbs bend at odd angles, disappearing into the surrounding landscape. They are creatures, free and wild, concerned only with each other and the joy of their surroundings: mud, wind, forest. But this sacred space snaps shut when Ray’s sister, Nessie’s mother Amanda, calls to tell Ray it’s time to bring Nessie home. Ray sheds her monstrous self. Her limbs shrink and her hair shortens. By the time she hangs up, she’s a human again: a young woman with obligations and fears, haunted by old hurts.

Transformation — the painful, non-linear, ongoing process of moving between worlds — is at the heart of the story. But it’s not merely a story told in smart dialogue and character growth. Lai literally draws transformation, and the feelings it evokes, onto the page.

Outside of their magical afternoons with Nessie (“little islands of solace”), Ray and Bron struggle to connect and communicate. Their shared love for her masks the cracks in their relationship. They fight about Bron’s depression, and Ray’s reaction to it. Their needs continually clash. “I can’t have you trying to fix me,” Bron says, in a beautifully drawn scene of uneasy domesticity. “I’m just wanting you to take care of me too,” Ray replies. Their home life is marked by silences and slamming doors.

The contrast between these worlds is stark. In one particularly poignant sequence, Ray, Bron, and Nessie are lying on a grassy hillside, their monster faces turned toward the sky, their legs waving in the air. “Thank you grass, for being soft for our bodies,” Bron says. “Thank you hill! For being slopey!” Nessie adds. Whimsy radiates off the page. Nessie unleashes wonder in her aunts, and Lai captures her doing it.

Lai represents the sacredness of queer aunthood with striking imagery: hair and skin that flow like rivers, claw-like hands reaching out to touch everything in sight, beings intertwined with nature, untranslatable. She subverts the old trope of queerness as monstrosity by making her monsters holy. But she also understands the limits of this kind of world. At the end of the above exchange, Bron says, “Thank you skin, for holding everything together.” Worlds cannot remain separate forever. The freedom Ray, Bron, and Nessie build together can’t truly hold them — or heal them — if they can’t also find a way to heal in the wider, harder world.

Bron, who is trans, and estranged from her religious family, makes an attempt to find that healing when she decides to visit her parents and sister for the first time in years. She leaves Ray, and it smashes open both their lives. Without the easy magic Nessie weaves between them, both women are forced to confront who they are outside of aunthood. Bron finds unexpected common ground with her younger sister. Ray turns to Amanda for comfort, and discovers that her sister is a whole person, with her own struggles, and not just Nessie’s overbearing mother. As Ray and Bron open up to their respective sisters, the seemingly-solid walls between the different worlds they inhabit begin to dissolve.

Lai depicts all of these relationships with so much tenderness. Conversations are as awkward and painful as they are in real life. Characters allow themselves to be seen one moment, but throw up humor as armor the next. Lai’s ability to articulate these nuances — in conversation, in character, and in the emotional intensity of the art — is mesmerizing.

Stone Fruit is a captivating journey through overlapping worlds. Queer worlds can be healing, but they can also suffocate. Queer aunthood is sacred, but it is not a savior. Relationships change, and end, but do not fail. Like so many queer people, Ray and Bron are trying to build something vast enough to contain all of who they are: their wild monster magic, and the harder magic that comes from loving, and being loved, in an unsafe world.

“You don’t have to be fun, magical auntie Ray,” Amanda says at one point, “you just need to show up.” As Ray and Bron learn to show up, they begin, slowly, to stitch the magics of their different worlds together into wholeness.

GRAPHIC NOVEL

Stone Fruit

By Lee Lai

Fantagraphics Books

Published May 11, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link