[ad_1]

The eight stories in Ling Ma’s collection Bliss Montage are linked, not only because their protagonists tend to be Chinese-American women on the brink of autonomy, or because they drift in the same sea of anomie and escapist fantasy. Rather, on a deeper level, these stories are bound by a subconscious connective tissue. Characters and images reappear across stories, bridging time and space, reality and make-believe. Friends and lovers leap in and out of guises, revealing trap doors in their personalities, inexplicable quirks in their daily habits. Nothing stays constant except the desire to transform.

Ma, the Kirkus Prize-winning author of Severance, writes if the past can be re-scripted, people reborn, as easily as a story is spun on the page. And indeed her stylistic versatility makes it appear that way. For instance, the unloved husband in the story “Returning” flies home to participate in a cultural festival, during which he buries himself overnight in the forest in order to wake up transformed. Anxiously, his wife wonders, “Would I even be able to recognize him when he emerged? What could he have possibly changed?” but the story ends just before she finds out. In all of these stories, Ma keenly captures the fantasies of young and not-so-young adults whose lives have plateaued, who feel estranged from their bodies, who think less about the person they married than about their joint assets. Never quite passionate in their love, secure in their finances, or successful in their careers, these characters find novel ways to rewrite their decisions.

On a formal level, Ma emphasizes this point by recycling images and “rewriting” stories. For example, the first and second stories in Bliss Montage share a narrator and antagonist, but they diverge in setting and style. The first story, “Los Angeles,” is a lighthearted, speculative romp that holds at its center an experience of domestic abuse. The second story, “Oranges,” presents a more somber, yet no less dreamlike, retelling of the same abusive relationship’s aftermath.

“Los Angeles” starts from a punchy premise. All the narrator’s exes live with her in the home of her rich husband, and they all hang out—eat Umami Burger, stroll through LACMA—until the exes are ready to move out and move on. This whimsical arrangement, however, belies a wound which Ma introduces in a deftly understated manner. “There are 100 ex-boyfriends,” Ma writes, “but two that really matter. Their names are similar: Aaron and Adam. Adam and Aaron. Aaron because I was in love, Adam because he beat me.” The story ends when a pair of cops nicknamed Tall and Short knock on the narrator’s door. They are looking for Adam. The narrator’s kids chase the wanted man from the house. The narrator runs after them and nearly catches her fleeing ex by his shirt.

In “Oranges,” the narrator, having moved on with her life, receives an email from another of Adam’s exes, who is collecting statements about his abusive behavior to use in court. This “unsurprising” revelation plays in the narrator’s mind as she follows Adam home, meets his current girlfriend, and reveals to her his history of abuse.

In both stories, the narrator follows Adam on foot. In the first, we get a fast-paced, comical chase: “The kids lead the way. […] They trundle through the house, gleefully jumping over sofas […] Kids! I yell. They punch through the door that leads to the back wing […] He went outside! the daughter yells.”

Compare that raucous scene to the subdued and sober opening of “Oranges”:

“Leaving the office one evening, I saw Adam coming out of the revolving doors of the residential building across the street. […] He held my gaze for a second, then pivoted away, heading down the street. […] His obliviousness emboldened me. We passed the train station. I kept a shorter distance between us. He would become smaller and smaller, almost dropping out of my sight, and then I’d quicken my pace and catch up. Just when I’d think I’d finally lost him, he would come into view again.”

In “Los Angeles,” the narrator pursues Adam because she is prompted by external pressures—the police, her kids. In “Oranges,” she follows him on account of a personal impulse. By letting this change in motivation take place over the course of two stories rather than one, Ma sketches a process of reckoning with trauma that is nonlinear and a portrait of the self that is fragmented over time.

Meanwhile, the image of a pillow serves as evidence of continuity across the two stories. In “Los Angeles,” the narrator mentions it in passing: “I washed the blood off the walls and the sheets. The splattered pillow I kept as evidence, not for anyone else, just for myself.” In “Oranges,” the narrator mentions it again as she burrows closer in time to the aftermath of the beating: “The lights weren’t on (he wouldn’t let me turn them on), so he couldn’t have seen the inflicted damage, or the blood on the pillow and the sheets, the walls.” The repetition presents a riveting lesson in contrasts: the emotional immediacy in “Oranges” reveals the degree to which the coolness and understatement in “Los Angeles” were pretenses.

Beyond formal experimentation, however, why write the story twice? To my mind, Ma reprises and retells the most important moments in Bliss Montage in order to depict the transformative effects of time. In the first instance of reflection, the true subject of the story is elided. The second iteration returns to the heart of the matter and tries to confront it. In a way, time passes in the white space between stories. Characters fall asleep and wake up. Like the husband who buries himself in order to change his life, Ma’s characters grow each time they reemerge.

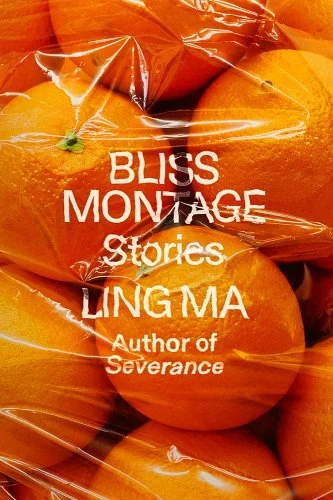

FICTION

Bliss Montage: Stories

By Ling Ma

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published September 13, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link