[ad_1]

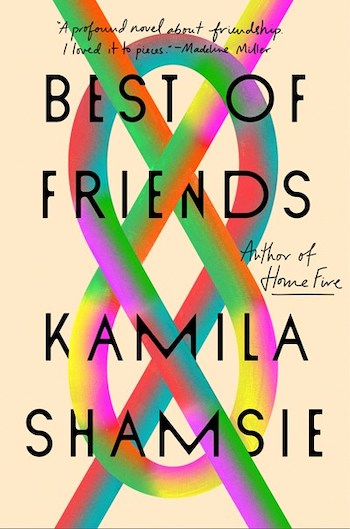

The best thing about Kamila Shamsie’s eighth novel, Best of Friends, is the story isn’t hinged on a friendship gnarled with sexual, bodily, or intellectual envy. The conflict is more nuanced, primarily marred by a class difference, but more implicitly by the contradictions that exist within a life-long friendship. At times, the characters feel as though “the forty years of friendship between them were just a lesson in the unknowability of other people.” But in moments of strife, it is “too easy, for each of them to draw blood; they knew; they knew all the exposed places, the armor chinks and the softness of the belly beneath.”

The first half of the novel is set in Karachi in 1988 during the final days of General Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship. The frightful climate of his reign, his sudden assassination, and the ascent of thirty-five-year-old Benazir Bhutto as the first female Prime Minister of Pakistan, contribute to creating a riveting backdrop to the adolescent lives of Maryam and Zara. Both are fourteen years old and in the same class at an elite school. Maryam is confident and belongs to an affluent family and hopes to inherit her cutthroat grandfather’s business, “Khan Leather.” At one point, wary of Maryam driving the family car without a license, her grandfather says: “It’s the only Mercedes of this model in all of Karachi.” Zahra, on the other hand, is diligent and comes from a family of little means. Her father is a forthright and self-made television cricket-show anchor, caught in a conundrum between his principles and the dictatorship, while her mother is a school principal. They are the kind of people who Maryam’s mother describes as “decent and hardworking.” While Zahra’s household attaches “honorifics or familial relations” to the domestic staff, Maryam believes “class positions overrid[e] deference between generations.”

The girls are aware of the class disparity and the afflictions of their respective social standings. But Shamsie uses this strife between class and desire as a catalyst in the development of her characters. It is, therefore, no surprise that Zahra grows up to be a highly scrupulous lawyer, while Maryam works for a profitable venture capital firm where she yields power by doling out punishments.

This portion of the novel is excellent. Zahra and Maryam are juggling family drama, school, the changes in their adolescent bodies, aspirations, and male attention. They are old enough to understand that there exists a subset of fear—”girl-fear”—but young enough to jeopardize their lives in an act of rebellion. A late-night incident in a car involving a character named Jimmy escalates the stakes, upends their lives, and closes their time in Karachi.

This is where the problem with the novel starts. The plot fast-forwards to 2019 when Zahra and Maryam are in their forties, living independent and ambitious lives in London. Every now and then, in the midst of an unrelated conversation, one of them mentions Jimmy. This seems forced, as if Shamsie is not confident in the connections she’s making in her story and that she must signal to the reader to remember what happened that night and to hold on to it until the chilling moments of confrontation that take place at the end. Shamsie could be granted leeway. Perhaps she wants to show that trauma works like a leaky faucet: it drips and deposits mold on the surface before it finally bursts.

But Shamsie’s portrayal of the episode with Jimmy isn’t convincing enough to make it believable that Maryam and Zara are still clutching on to it after three decades. Even though the scene is thrilling, the fear palpable, the stakes heightened—it’s never to the point where we comprehend it to be the ultimate wound.

The second half of the novel is also rushed. Shamsie doesn’t pause to leisurely explore connections or illustrate characters in deft strokes. Instead, she tries to tie in political issues to their motivations, leaving us with a distracting plot and a weak narrative arc. When the novel ends, you can’t help but wonder how Maryam and Zara sustained their friendship for as long as they did in spite of deep-seated resentment. Shamsie answers this in the very first pages: “Perhaps that was the key to the longevity of childhood friendships—all those shared subtexts that no one else could discover. And perhaps shared subtexts felt even more necessary when you both lived far away from the city of your childhood and that was itself the subtext to your lives.” Yet this subtext flounders at the first instance of conflict and the subtleties Shamsie effortlessly creates in the first half of Best of Friends dissolve like Zahra and Maryam’s friendship.

FICTION

by Kamila Shamsie

Riverhead Books

Published on September 27, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link