[ad_1]

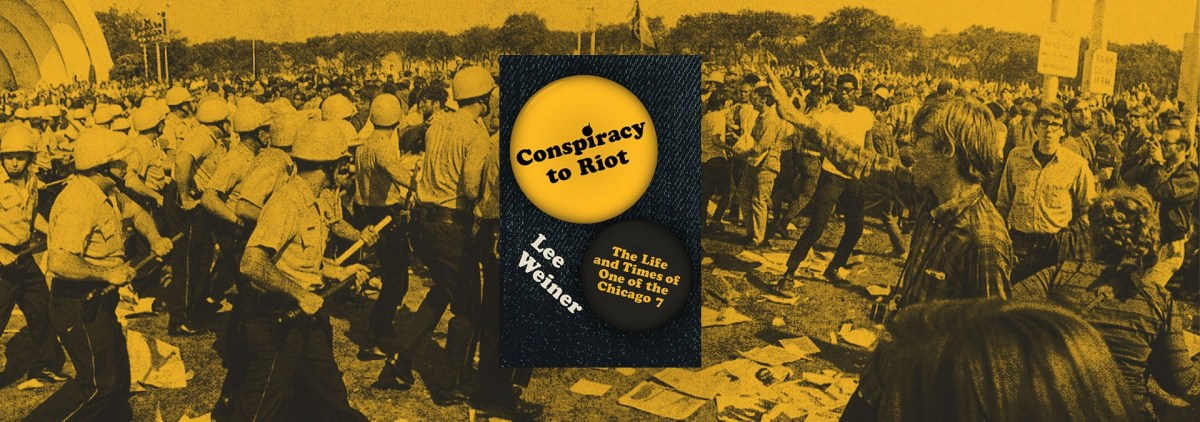

Lee Weiner was one of the infamous Chicago 7, whose trial became a cause celebre for the left during the manic year of 1968. Weiner was also the only one of the group who actually hailed from Chicago, and whose public profile was smaller than his comrades Tom Hayden and Abbie Hoffman. His memoir Conspiracy to Riot: The Life and Times of One of the Chicago 7 tells his side of the story, marking his “coming out of the shadows” after years of relative obscurity. Weiner’s account illuminates both the relevance of the Chicago 7 as well as some of the limitations of their flamboyant activism.

Weiner describes himself as a bookish, inquisitive Jewish kid from the Chicago’s South Side. Growing up in the fifties, it didn’t take much for Weiner to see the injustice embedded in American society. While studying sociology in college, Weiner saw firsthand the degraded conditions of the Cabrini-Green projects and became a natural community organizer. He met and befriended activists like Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman.

By 1968 the war in Vietnam had become a fierce national debate, and the Democratic Party was sharply divided between the establishment candidates and the far left, a contrast that is very much still with us today. The two major groups who planned big protests outside the 1968 Democratic convention were the Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam and the Youth International Party, or “Yippies.” By Weiner’s estimation this bunch seemed endearingly flaky, hanging out in designated zones, and offering free food, music, arts and crafts, and fliers. The City of Chicago, however, made it clear that they had no intention of granting a bunch of hairy doped-up freaks permits to peacefully protest or demonstrate, and so the scene was set for a clash between protestors and cops.

Like many others, Weiner was tear gassed during the riots and observed firsthand cops beating protestors, which was infamously captured live. Amid all the chaos, Weiner says he didn’t do anything violent or destructive. But when an undercover cop overheard Weiner casually remark to some friends that the contents of his car, with its “gasoline, empty soda bottles, dirty clothes, and high phosphate laundry soap” could be used to do something about reclaiming ownership of the streets, his troubles had only just begun.

The indictments he was served accused him of a “conspiracy to cross state lines to do terrible things during the convention in Chicago the year before.”

It’s useful to have Weiner’s account of the trial, which seemed intended to make a very public example of the kind of treatment those long-haired freaks could expect to receive if they started protesting. Celebrities frequently dropped in to observe the trial and Groucho Marx, of all people, said that being a witness for the defense would be “an honor” but wisecracked that his last name might be a liability.

The trial at times does sound a little like a Marx Brothers movie, with the defendants cast as a rambunctious bunch of merry pranksters caught in a situation they couldn’t banter their way out of. Judge Julius Hoffman sometimes comes across as the epitome of the grumpy square from a TV sitcom. He’s constantly red-faced, banging his gavel, telling everyone to shut up and sit down whenever they got out of hand. Which, to be fair, the defendants often did. Weiner was one of the quieter defendants, but there were heated debates in private about the most effective defense strategy and the trial’s larger political implications.

Luckily, Weiner was finally found not guilty of what he hadn’t actually done. After the trial, the Chicago 7 ended up going their separate ways and in some interesting ways the radical insurrectionary spirit of ‘68 ended up adapting to changing cultural attitudes.

To his credit, Weiner admits that Nixon was elected in 1968 partially because he promised “law and order” (a frighteningly thinly veiled threat then and now) and because enough mild-mannered voters were turned off by all the violence in the streets and didn’t like or trust the freaky hippies very much, let alone listen to the arguments they wanted to make.

Which may actually provide a useful lesson for today.

The violent insurrection of January 6 indicates a crucial and possibly permanent change in the current political landscape. In Weiner’s day, it was the far left who loved acting out and being outrageous. The countercultural left was much more open to occupying buildings, conspiracy theories, and “revolution for the hell of it,” as Abbie Hoffman once wrote. Now, the far right has mutated from the buttoned down Nixon-era Silent Majority types into hooligans who embrace a raucous, sarcastic, in-your-face attitude towards the snobs and squares. It’s now the left who is concerned about accurate information, detailed policy proposals, and ethics in government. In a way, Weiner’s post-trial life is an example of this shift since he went on to become an academic, eventually earning a couple of master’s degrees and a PhD in Sociology.

Looking back on the trial and the generational convulsion it was a part of, Weiner refreshingly doesn’t swear off his old allegiances or political ideals. He clearly hasn’t moved to the right in his autumn years, though he is perhaps a bit less sanguine about the potential for radical change.

It’s heartening that Weiner doesn’t think all his efforts were in vain. Here’s what Weiner has to say about his participation in history, with all the benefits of hindsight: “While a political life isn’t easy, and while frustration, anger, disappointment, fear, and confusion are sometimes pieces of it, I believe there is no more self-respecting, fulfilling life to try to lead.” Amen to that. Or, as they used to say, right on.

MEMOIR

Conspiracy to Riot

By Lee Weiner

Belt Publishing

Published August 4, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link