[ad_1]

Margot Highsmith is 30,000 feet in the air, crammed into the airplane bathroom dabbing at a bloody lip she hadn’t realized was bleeding. Behind in New York: family despair and romantic anguish that might actually just be humiliation. (Sometimes it’s hard to disentangle the two.) But outside of Bozeman, Montana is an empty house and no one she knows. Margot plans to stay indefinitely.

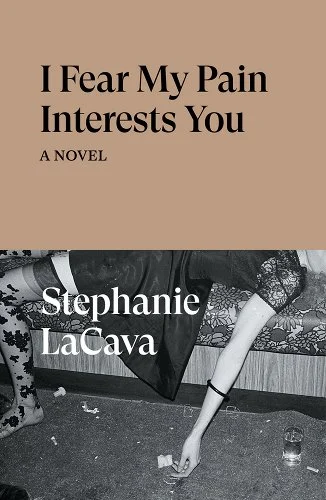

So begins I Fear My Pain Interests You, Stephanie LaCava’s new novel which considers what it means to be a woman in the world, as well as pain, sex, fear, corporeal or otherwise, and maybe even love as well. The story moves between timelines—between Montana and everything that made Margot run there. The daughter of two celebrity musicians too busy to notice much, she was raised by her grandmother, a woman bent on maintaining a certain kind of life befitting the size of her bank account and the social role she has long held. Margot had a bohemian childhood, spent first on tour (“toted [] around for years, like luggage”) and then in a little town outside of New York City, her grandmother’s domain. But Margot is famous too, unwillingly at first and then somewhat by choice. A particular birthmark has been fixed forever in the public domain via a series of paparazzi photographs. Later she takes up acting, with her grandmother overseeing her roles. Cue the smoking and partying and the obfuscation. Poor Margot: young, wealthy, forgotten, destructive. Her life is one misstep after another tragedy.

It’s a familiar trope, the unhappy and harmful rich girl, only Margot can’t in fact feel pain; she suffers from congenital analgesia, a rare disorder which prevents a person from registering physical pain or temperature. As such, she also doesn’t sweat. Childhood scrapes generate no reaction. Falling off a heap of instrument cases, Margot smashes her kneecaps, but it is only after someone notices the blood-stained tulle dress that she realizes something is wrong. And even then, it isn’t pain she feels but awkwardness: “I felt nothing but embarrassment…the throb of prying eyes.”

In Montana, Margot moves into the empty house of her friend Lucy’s late father, a famous film critic. It is dilapidated but beautiful and big. No one had stayed there for years. For the first week, Margot barely moves or eats. “Self-pitying and pathetic, my curiosity restrained by fear and sadness.” After six days spent lying on the floor, she shifts to a mattress and begins to consume the bars she brought with her and candy she buys at a store in town. Her only new acquaintances are birds in a cemetery. For three weeks and three days she interacts with no one, save for a daily phone call with Lucy. Then she meets Graves at a graveyard.

We give ourselves so completely over to first love and can never do so in quite the same way again because we know the pain. And still we try—because we have forgotten. No pain may mean fearlessness, but it can also make one reckless, which is perhaps why Margot jumps so quickly into a relationship with Graves. He is creepy and domineering. He refuses to share his real name (hence Graves), reveal much about his murky background, or maintain healthy hours. Together they watch movies and then have sex or have sex and then watch movies. He is also the first to name Margot’s condition for her. In fact, he is fascinated by her congenital analgesia. Nothing good can come from this.

The women LaCava writes—Margot here, Mathilde in The Superrationals, and herself in her memoir—are vessels for the projections of others. Margot knows this, she knows how mutable identity is, how easy (and necessary) it can be to shapeshift. She pretends not to know things to appease the men she dates. She wears outfits set out by Josephine. Describing the posters she had created to decorate her dorm room, Margot says, “I liked the 80s computer graphics, and sometimes, less sincerely, the pop band ones. It’s weird how kids of a certain age recycle these styles and personalities while trying to figure out their own.” Such lofty language for someone who is barely beyond the teenage years herself. To be a teenager, or even in one’s early twenties, is to exist in a plastic period where one’s sense of self is at its most malleable.

But Margot is also hard to grasp because LaCava’s writing is so economical and spare. Or maybe Margot can’t be grasped so LaCava must be dispassionate. Much is withheld, which can make for elegance but also iciness. It’s hard to know how to feel about I Fear My Pain Interests You. Very few of the sentences are gripping, but then why keep reading? Is Margot interesting because she lacks pain or despite that? So much of being young is believing in one’s own invincibility and the urgency of existence. We all rush towards things, at times just for the experience of them. To lose that acceleration—that force of being—is one of life’s great losses. It’s hard to move so quickly, so courageously as experience accumulates like a carapace. But then of course there’s the other side too: If you can’t feel pain, then protection is almost impossible.

FICTION

I Fear My Pain Interests You

By Stephanie LaCava

Verso Fiction

Published September 27, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link