[ad_1]

Perhaps there are no more famous witches than Shakespeare’s three “weyward” wenches. The crookedness of the Bard’s (and Britain’s) witches represented a cultural fear of an empty womb—the childless, the menopausal. Women were to be coupled and birthing. If they were not, they were witchy. Evil. Monstrously magical.

But, for the reader, the witches in Macbeth are delightful. They are our gnarled soothsayers, our framework, and our tour guides. Their craggled rhyme scheme is pleasurable. While childless, Lady Macbeth is not regarded as a witch in Macbeth. Still, she’s monstrous in her murderous plots aimed for the throne. Lady Macbeth represents a Shakespearean “weyward” witch as she craves a masculine power that extends beyond the conventional idea surrounding a woman’s identity: married and childbearing.

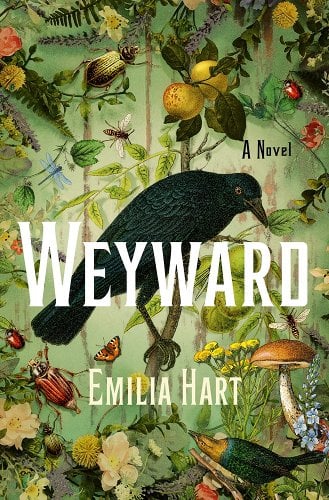

How might we regard a witch now? Emilia Hart’s debut novel, Weyward, explores female independence today, sixty years ago, and during the 17th-century British witch trials. Alternating between three separate storylines, Hart examines the women in the Weyward (née Ayers) family line and how both literal and figurative witchdom defines their lives.

Our modern witch, Kate Ayers, kicks off the novel in a desperate escape from her abusive husband, Simon. Through a carefully crafted disappearing act, Kate finds refuge in the fictional town Crow’s Beck. Kate recently inherited a country cottage from her late Aunt Violet, a fact Kate conceals from Simon. Settling into her dead aunt’s house, Kate seeks to uncover who this estranged, unmarried, and childless woman was in life. Violet is particularly interesting to Kate. The reader learns that Kate is newly pregnant with Simon’s child, and she must wrestle with the consequences of whether to have the child or not, all the while hiding the pregnancy from Simon. Violet serves as an inspiration.

A sheltered teen hidden away by her father, Violet carries the second timeline, which proceeds throughout 1942. With no friends and little exposure to the real world, Violet naively puts herself into a dangerous situation when she takes a walk in the country with Frederick, her alcoholic cousin who is a soldier on leave. Frederick rapes his cousin, defiling Violet emotionally and sexually, making her unfit for marriage. This complicates the situation with Violet’s father, who would like to marry Violet off. Violet is already suspicious that her father is withholding information about Violet’s mother, who allegedly died giving birth to Violet’s brother. But as Violet starts to ask questions and locate answers, she finds that her mother’s story isn’t accurate. After a doctor reveals to Violet’s father that she is “no longer intact,” Violet is sent away to her mother’s secret country cottage in Crow’s Beck. Here, Violet seeks to uncover the mystery of her mother’s life (not unlike Kate for Violet).

Hart goes to great lengths to situate Violet as strange and different. Violet has a pet spider named Goldy and a fondness for insects and crows. The reader is given the sense that Violet’s natural connection is a witch’s tendency, especially given the town’s name, Crow’s Beck. Kate’s transformation from a run away victim to an independent woman will eventually lead to a connection with creepy nature, as well. Indeed, it should be noted that the witches in Hart’s novel are not just figurative; rather, they are women whose magic thrives in independence. We do not, however, get a clear picture of this witchdom until later in the novel.

Our third Weyward witch narrative is set in 1619. Altha is on trial for the murder of her childhood friend Grace’s husband. We aren’t sure if Altha is truly a witch, but she scrubs away a “third nipple” located on her ribcage, a witch’s mark according to local lore, to secure her innocence. While we experience the tension and fear of waiting for the jury’s verdict along with Altha, we can’t know until the end of the novel if Altha really committed the things she’s tried for. As Altha awaits her sentence, time shifts back further, quietly, sneakily, and Hart reveals Altha’s gift as a healer (the meaning of her name) as she works with her mother, who is unmarried. With her mother’s untimely death, Altha takes over as the healing resource in Crow’s Beck.

The timelines unfold with the same narrative themes: Kate’s secret pregnancy prompts her escape from Simon, Violet’s conception occurs after Frederick rapes her, and Altha’s childlessness coincides with Grace’s inability to carry a child. The Weyward witches’ connection with insects and crows eventually aligns with herbal-induced abortions. With this effort, Hart further fixates on the witches’ ability to control life and death, the very idea harkened from Shakespeare’s time. In Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Hart’s Weyward, being a witch is powerful and desirable, yet terrifying.

While it’s fun to read about witches, the purpose of the Weyward witches feels somewhat unpacked. Since we aren’t certain that the Weywards are witches until halfway through the novel, the discovery feels more like confirmation rather than revelation. Hart renders a suspenseful and pleasurable story, but the reader is left wondering about the narrative importance of whether or not the women are witches. What does it mean that these women can commune with insects and crows? Must they be witches to be independent? I don’t believe that latter point is Hart’s agenda, but the late revelation flattened the potential for witchdom to have the feminist effects the book aims for.

Kate’s story slightly dominates the novel, and yet it feels the least surprising. Hart does a lot of work to validate why Kate stayed with Simon, a man who, like most of the men in the novel, is villainous in every sense of the word. Likewise, Grace’s husband is singularly abusive and cruel, while Violet’s father is passive, irritated, and eager to do away with his daughter when she gets pregnant (it almost seems as if he wanted this result, but this is unclear). The men are so evil and terrible that at times the book can feel rather didactic.

Still, Hart’s writing is stunning. She writes with grace and control, illuminating the critter world around the women in a delightfully creepy way. Perhaps Hart’s greatest strength is her ability to harness suspense. While Kate’s storyline often feels familiar in the depiction of victimhood, Altha’s does not. The trial scenes are rendered with urgency and fluidity, as Hart moves between Altha’s first-person perspective and the testimony. The most gripping moments of the novel come at the end, and I won’t spoil them. Kate’s story ramps up at the moment she embraces her witchdom, as does Altha’s when she, too, turns to her inner witch. Violet’s story, however, is underdeveloped: a shame, since her exiled life had the most original concepts. When depicted both figuratively and literally, Hart’s witches harness an inspiring feminine power.

FICTION

Weyward

By Emilia Hart

St. Martin’s Press

Published March 7, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link