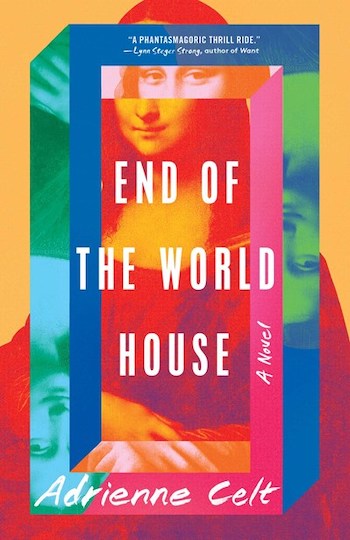

[ad_1]

At the end of the world, Kate is Bertie’s best friend. In the aftermath of a world war, after enduring terror and loss together, they still have each other. Until Kate decides to move away—and Bertie is left to grapple with her own personal apocalypse. In End of the World House, Adrienne Celt delivers an apocalyptic mindset without sinking too deeply into despair. Through her characters’ devotion to one another, across different timelines, she leads her readers through a world that is always on the edge of ending.

As a last hurrah before Kate’s move to Los Angeles, Bertie and Kate take a trip to Paris. The frivolousness of a vacation in hard times isn’t lost on them, but it’s the new normal. They choose Paris because “they felt that the French advertisements did the best job of flirting with the overall sense that the world was ending without ever actually stating outright that this might be your last chance for a vacation.” It’s a last chance for joy together, in more ways than one.

After so much impossible grief, both in Bertie’s personal life and in the world around her, Bertie can’t imagine how she’ll handle the loss of Kate. Without Kate, after all, “who would hold her together?” In the spirit of the apocalypse, she doesn’t see Kate’s departure coming until it’s already upon her, and by then it’s too late.

After Bertie and Kate arrive in Paris and accept a mysterious man’s invitation to visit the Louvre while it’s closed to the public, the days start to get strange—which is to say, they start repeating. After swirling through copycat mornings—racing through the rain, arriving at the Louvre, wandering the empty halls in fresh awe—Bertie and Kate ultimately lose track of one another. They slip into different time loops.

Bertie clings to her friendship with Kate as tightly as ever, so she does everything she can to reunite with her best friend. Instead, she finds Dylan.

He slips into Bertie’s world sneakily, immediately forging space for himself where there was none before. “‘Hi Bert,’ he said, and took her hand… He was—who? She knew who he was. He was Dylan, her boyfriend.” Bertie’s already fuzzy memory undergoes greater pressure as time loops bend around her.

Celt tightens the laces of the story when Bertie finally makes her way to a locked door in the Louvre, on the other side of which, she believes, is Kate. It’s then that Dylan and Bertie strike a deal—to get back to Kate, Bertie can give Dylan a year of her life in a different time loop, one where they’re in a relationship.

There’s confusion in the two alternate timelines converging in Bertie’s mind, and Dylan and Kate seem to cancel each other out in Bertie’s memories. Dylan was a boy she kissed once in high school, “but they hadn’t spoken again after that. Not for years. She hadn’t seen him until today. Except she had. Yes and no. Kate and not. Paris, France, and the end of the world.” He’s appeared inexplicably in this reality, and if he’s the most important person in Bertie’s memory, Kate can’t be.

Dylan explains vaguely that he has powers to manipulate time loops, and he can make an alternate timeline (one with him in it) feel normal to Bertie. But it never quite feels normal to the reader. There’s some friction in Bertie’s acceptance of this other life she could live, while the reader, knowing everything, is unequivocally predisposed to favor Kate.

Dylan’s deal feels like an uncomfortable imbalance of power, one Bertie isn’t aware of but one that comes across as predatory nonetheless. “I want the whole thing,” Dylan says. “That would be the deal. We go back, and we live our lives for one more year… It won’t be so bad.”

But “it will,” Bertie says. “It is.” Dylan solidifies the feeling of a trap when he answers, “‘But what choice do you have?” Bertie knows “she had no choice at all.” Yet even in this alternate version of her life, while she does come to value and love her time with Dylan, the love she has for Kate is unshakeable.

Celt writes Bertie with such earnest detail and depth that her love for Kate truly does feel like a force large enough to keep the apocalypse at bay. Part of why this love feels true is because the world around it feels true, even as it’s falling apart.

Throughout End of the World House, there’s a sense of something wrong in the periphery. Celt’s prose is light, at times unnervingly buoyant as it dips in and out of Bertie’s trauma. Reminders of the state of the world slip into Bertie’s consciousness and work their way around an existential crisis until something mundane and tangible pulls her out of it. “Things that had always seemed permanent came tumbling down like dominoes,” thinks Bertie one morning. “If one storm could knock out the country’s access to oil, how vulnerable were they? Where else could they be hit? The coffeepot beeped, then flooded the first cup.” Like so, Celt brings us back into the present, over and over again.

Bertie is living in a time loop, but most of the time she isn’t aware of it. In some versions of her life with Dylan, missing Kate is something she hasn’t actively done in years. Through it all, Bertie is persistent in coming back to her art. She’s a cartoonist working for an ad agency, and almost unconsciously, Bertie’s dormant love for her friend works its way into her imagination.

Even when she’s far from Kate and that friendship is an echo at the edge of Bertie’s knowing, the idea of an End of the World House remains. “Bertie and Kate had made plans to buy a house together in the countryside, for when things started to get really bad.” It’s a pastoral fantasy: “End of the World House, they would call it… Inside, light would stream through the windows, bending past gauzy curtains to fall on empty coffee cups and stacks of books. None of the kitchen cabinets would quite close. There would be old furniture…” Like many fantasies, it was always impractical, but it kept Bertie and Kate company when they needed it.

It’s an impossible yet precious idea, and it’s one Celt allows Bertie to choose repeatedly, no matter what timeline she’s in. The consistent inner knowing of her love for Kate gives her strength. “That was how art, how anything, became immortal,” Bertie thinks once in the Louvre as she wanders through the halls. “Becoming a still point in the universe, around which endless bodies revolved.”

End of the World House is a post-apocalyptic novel that holds the persistence of the everyday. It’s a book that offers a deep look into coping with loss, endings, and change, but most of all, it offers a deep look into Bertie’s character and allows the audience to live with her through a myriad of different lives, through the ending of so many worlds.

In End of the World House, the apocalypse is secondary. Whether or not the world ends, whether or not the love works out, the love matters anyway—in whatever form it’s allowed to exist, it lasts.

FICTION

by Adrienne Celt

Simon & Schuster

Published April 19, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link