[ad_1]

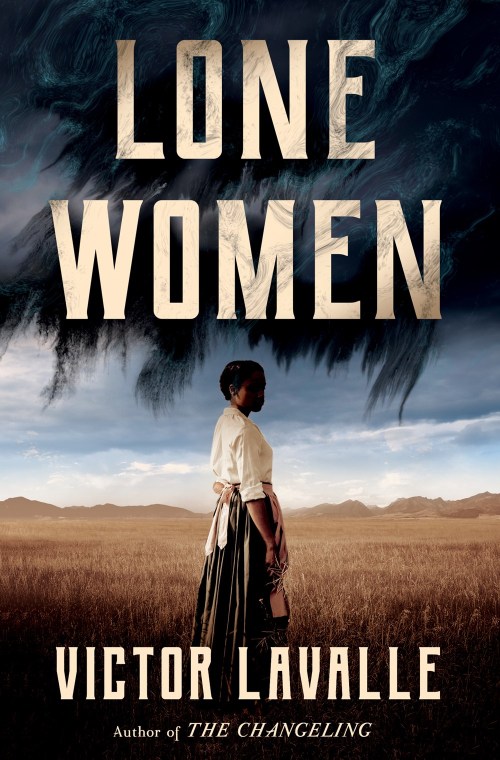

The Western, as a genre, is rife with horrific elements: its frequently alienating landscapes, its history of violence, and its strange and unrestrained collision of cultures. In Lone Women, Victor LaValle takes horrors both human and supernatural as his subject: a haunted vision of the American dream that accelerates into a bloody exploration of monstrosity and survival.

After the death of her parents in 1915, Adelaide Henry heads to Montana to “prove up” a homesteading claim. Taking advantage of the government act that allowed anyone a land grant—even an unmarried Black woman—if they could turn it into a working farm, Adelaide tries to leave behind her troubled past, hoping that there’s space for her secrets in big sky country. Dragging along an enormous locked steamer trunk—one that obviously contains her most troublesome secret—Adelaide attempts to start anew outside the little town of Big Sandy. Local elites and self-serving philanthropists reveal themselves as the local instance of much larger antagonism and bigotry, while Adelaide wrestles with her own secrets, the more immediate problems of survival in the bleak Montana landscape, and a gang of murderous bandits.

Adelaide comes to Montana seeking a fresh start, a blank slate. But this is already a storied landscape, one actively over-written and revised by waves of colonists. She is not the first Black person to come to Big Sandy; Chinese laborers and other immigrant groups laid the conditions for the town, and there is always the question of the original, Indigenous inhabitants. “Buildings like the opera house were erected to erase their memory.” While Lone Women works at small-town and interpersonal levels, LaValle is sharply focused on the construction of biased history, and the enforcement of race and gender norms, as active projects, and captures both the comic smallness of his bigoted villains and the very real horrors they perpetrate and perpetuate.

LaValle leans into the inhospitable nature of his setting: survival in this landscape seems all but impossible. That background of desperation, of the high chance of death by exposure if things go wrong, loads the stakes for the novel’s human conflicts. And while the novel circles just a few key storylines, it nonetheless manages to express an immense vastness, a sense that there are larger and more complex stories continuing on, out beyond the firelight. While Adelaide’s personal monster holds the novel’s focus, it’s not the only supernatural element—ghosts, in particular, seem to populate this vision of the West, hinting at old crimes and eerie histories.

Despite these hostile surroundings, and the increasingly-clear danger posed by many of the town’s inhabitants, Adelaide is not alone in Big Sandy, and her unexpected allies come to define the book. Outcast teachers, distillers, workers, they’re the women written out of the popular history-books, but still persisting, and here shown vital, defiant, and eventually triumphant. It’s hardly a new observation that the Western, as a genre, has an ahistorical problem in its white, male, and cisnormative vision; Lone Women does a particularly satisfying job deflating that project.

One of the most striking elements of the Lone Women, on a textual level, is LaValle’s use of repetition. His characters often seem trapped, looped, using mantra-like phrases to avoid confronting some awful aspect of reality, or to assert a desired one. It lends the novel an unsettling chant-like quality at times, and always seems anchored in the characters’ deepest hurts and fears; a larger and eventually hopeful theme of the book is the way these repetitions are first interrupted and then abandoned. Coupled with LaValle’s gifts for jarringly good imagery and clean, suspenseful plotting, these echoing phrases give a haunting and human dimension to the wind-scraped setting.

Something about the pacing of the novel didn’t quite match up, for me, with its tone and atmosphere. The very short chapters, constant action, and frequent point of view shifts seem slightly at odds with its spacious background and the way that Adelaide’s goal—starting a successful farm in an inhospitable place—is such a long-term project. It does make for a very propulsive book, with a surprising set of subplots and supporting characters converging at a rapid, twist-packed pace. And, around the halfway point, it becomes very clear that whatever lurks in Adelaide’s trunk is not going to remain ambiguous: it’s going to get out.It’s still tempting—and not, probably, wrong—to read Lone Women’s monster metaphorically, as personal trauma, as the history of racial violence come calling. Where the novel shines, though, is in how it embraces its non-metaphorical nature, in the literal reveal. Once Adelaide and her allies come to grips with reality—not what they feared it was, not what their oppressors claim it to be—Lone Women shifts yet again, positively reveling in righteous revenge and an almost utopian turn: a bloody reclamation of the frontier’s promise.

FICTION

Lone Women

by Victor LaValle

One World

Published March 28th, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link