[ad_1]

I was lying in a hospital bed and, according to my doctor, there was a good chance I wouldn’t make it through the night. I’d been having massive intestinal bleeding and they couldn’t pinpoint the source. I thought of my children, and the prospect of not seeing them grow up, of the beautiful palm trees outside, and the bright blue sky that I might never again glimpse. And then, I thought of Stephen Hawking. That might seem an odd turn to my stream of consciousness, but I was in the midst of writing my second book with him and had been working with him for years. Working with Stephen, death was never far away but that was supposed to be his death, not mine. His illness, ALS, kills you by destroying your motor neurons, which reach from the brain to the spinal cord, and from the spinal cord to the muscles throughout the body. When the motor neurons die, the ability of the brain to initiate and control muscle movement is lost. That leaves you subject to repeated lung infections, with life or death situations on an annual basis. I, on the other hand, was a (usually) healthy and relatively young person. But Stephen was full of surprises, both in physics and in life, so I was thinking it would be just like him to outlive me after all. He was an Iron Man in a fragile man’s façade.

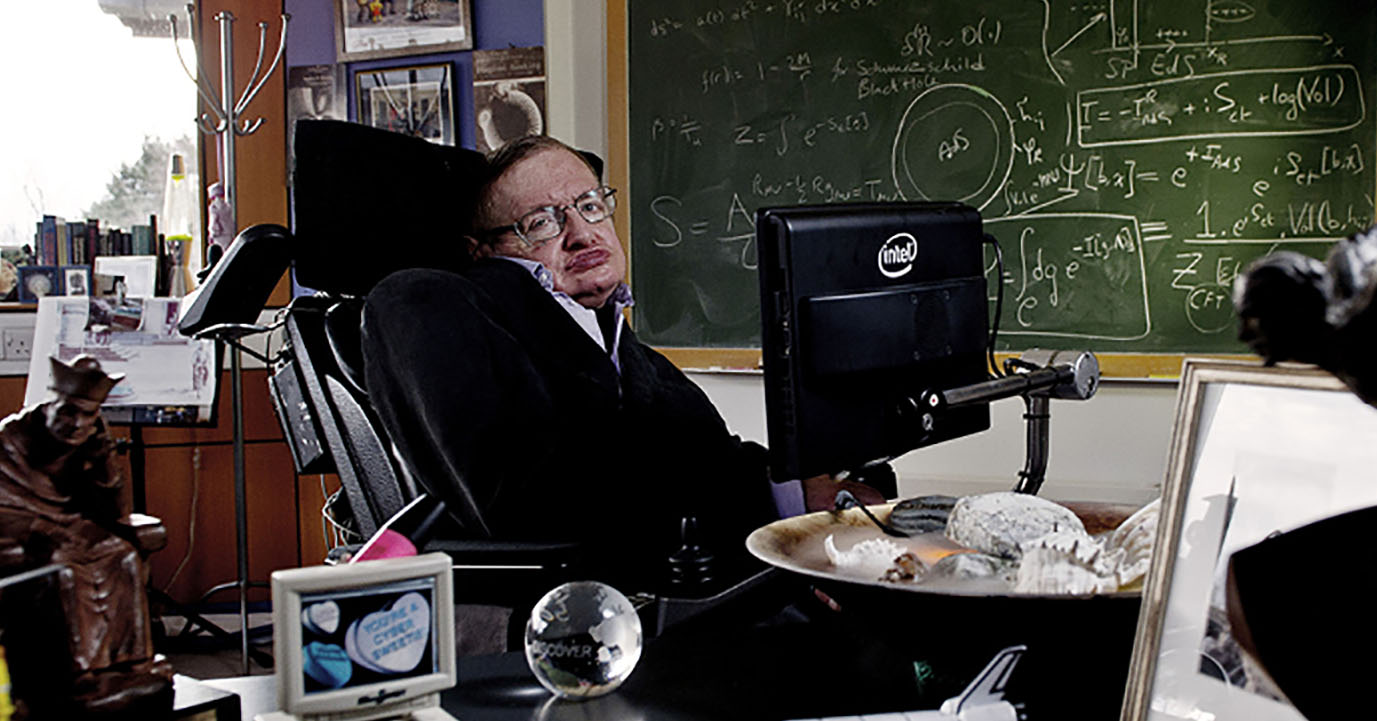

We talked about my brush with death when I saw him next. He liked to make bets. I told him we should be bet on which one of us will die first. He frowned, his way of saying “no.” That was easier than typing it out so his computer could voice it for me. To type, he’d have to twitch his right cheek at just the right moment. His glasses had a sensor that detected the twitches and translated them to mouse clicks, which allowed him to select letters, words, or phrases from lists as the cursor moved around on his screen. When he was done, he’d select the “speak” command in a similar fashion. It was something like playing a computer game.

I asked Stephen why he didn’t want to bet on our deaths. This time, he typed out his answer. It was a single sentence, but it took him more than a minute to compose it. “The loser won’t be around to pay,” he said. He always was one step ahead of me in logical thinking.

People often asked me what it was like to work with Stephen Hawking. It was an honor of course. And I learned a lot. But what I learned had less to do with the equations on his blackboard or his research papers than with the simple drops of sweat that I would watch rolling down his forehead, and then his cheek, on a hot summer day. None of us like the subtle tickle that creates, and so we blithely wipe it away. But Stephen couldn’t wipe it away. To Stephen, a drop of sweat was an atom of Chinese water torture. Or it would have been, had his will been weaker. But rather than be tortured, he taught himself to accept the sensation and to overcome the annoyance of the tickle with the strength of his mind.

Similar challenges faced Stephen moment after moment. Not being able to write down equations was a severe handicap in doing physics, and he was famous among his physics colleagues for adapting by learning to think geometrically—in pictures. Less well known was the torture of lying in bed at night and not being able to turn when needed for comfort to alleviate some ache that develops. Or the morning ordeal of various medical treatments, and of being bathed, dressed, and fed, which took hours. As one of his carers told me, “When I came off shift and he was still alive, I felt I’d done a good shift. Because he was alive. Because I’d kept him alive.”

I don’t know what Stephen’s reaction would have been to this pandemic or society’s reaction to the lifestyle changes it imposes on us. People complain of having to wear masks; Stephen had to spend each night on a ventilator lest he suffocate in his sleep. When the limitations required by the pandemic start to get me down, I think of Stephen’s example. I think of the courage he needed to simply show up at the office each day. I think of how, despite all the hardships, he maintained a positive outlook and a sense of humor. Spending time with Stephen taught me to be more tolerant of the problems in my own life, and to be more grateful for all that is good, however small. To be Stephen’s friend was to realize that we need not wait for a debilitating disease or have a near-death experience to resolve to make the most of our time on earth, and to make the best of whatever circumstances engulf us. He’s been gone for more than two years now, but like his physics, that life lesson endures—we can overcome anything; even having to wear masks and keep our distance from others.

Author Photo: Ralph Adolphs

-

Featured Book

Stephen Hawking

Leonard Mlodinow

One of the most influential physicists of our time, Stephen Hawking touched the lives of millions. Recalling his nearly two decades as Hawking’s collaborator and friends, Leonard Mlodinow brings this complex man into focus in a unique and deeply personal portrayal. We meet Hawking the genius, who pours his mind into uncovering the mysteries of the universe—ultimately formulating a pathbreaking theory of black holes that reignites the discipline of cosmology and paves the way for physicists to investigate the origins of the universe in completely new ways. We meet Hawking the colleague, a man whose illness leaves him able to communicate at only six words per minute but who expends the effort to punctuate his conversations with humor. And we meet Hawking the friend, who can convey volumes with a frown, a smile, or simply a raised eyebrow.

Mlodinow puts us in the room as Hawking indulges his passion for wine and curry; shares his feelings on love, death, and disability; and grapples with deep questions of philosophy and physics. Whether depicting Hawking’s devotion to his work or demonstrating how he would make spur of the moment choices, such as punting on the River Cam (despite the risk the jaunt posed), or spinning tales of Hawking defiantly urinating in the hedges outside a restaurant that doesn’t have a wheelchair-accessible toilet, Mlodinow captures his indomitable spirit. This deeply affecting account of a friendship teaches us not just about the nature and practice of physics but also about life and the human capacity to overcome daunting obstacles.

[ad_2]

Source link