[ad_1]

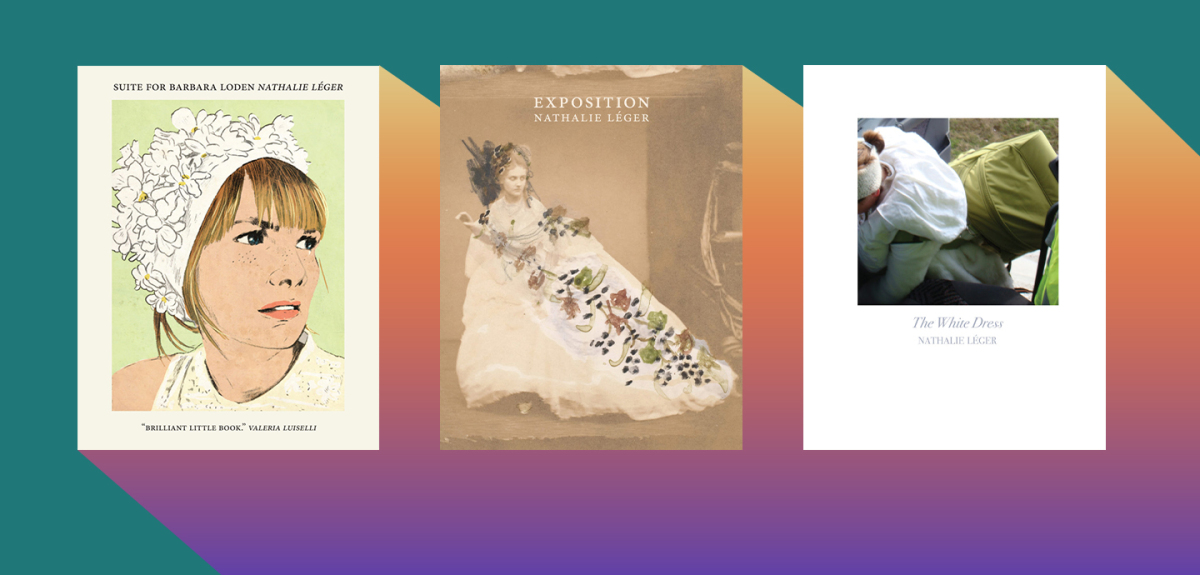

When asked about her triptych, now translated in full from the French and published by Dorothy Project, Nathalie Léger suggested that her intention was to “try to rescue the words of a woman who couldn’t utter them herself.” Indeed, Léger’s three books give voice to many women: The Italian aristocrat Countess of Castiglione in Exposition, American film actor and director Barbara Loden in Suite for Barbara Loden, and Italian artist Pippa Bacca in The White Dress. For Léger, the work of “rescuing words” is, in part, a project of plunging into the archive to unearth the forgotten, castigated, yet noted women of history, waylaid by both time and the men who controlled their narratives. While these women, infamous and maligned, anchor each book, Léger’s triptych reveals a project less concerned with individual stories than with the larger context by which we recognize them. All of her figures — the female director, the performance artist, the most photographed — themselves become vehicles through which Léger tells a more local story of her mother and, most significantly, a story of forgetting.

“Let us admit for a moment that forgetting was invented for killers,” writes Léger in The White Dress, the last book in her triptych, which takes as its subject the Italian performance artist Pippa Becca, who was raped and murdered in 2008 while hiking across Europe in a wedding dress. The purpose of Becca’s project was at once idealistic, rooted in a desire to spread goodness, seeking to repair the world by showing up in a white dress, a symbol, for Léger, of both naiveté and undisturbed innocence. And yet, The White Dress is not interested in idling on Becca’s intentions or the grandeur of her project. Instead, Léger lingers with the performance artist’s desire to mend something that was out of proportion in the world — and her ultimate failure to do so. Léger places Becca’s failure alongside a history of performances which her mother could have equally given: her mother would scrub the grass in front of the courthouse in her wedding dress; she’d pull a block of ice along the seafront until it melted; she’d let the paint trickle out of a pierced can as she walked through the city; she’d make a scene; she’d be seen. The paralleling of these actions gestures towards a central line of investigation for Léger between the highly visible performances of these women, their suffering exhibited openly, and the inaction of her mother, whose suffering is shouldered in silence.

The opening of the first book in Léger’s triptych, Exposition, begins with a call to “neither discern nor dissect” the material of the archive but, rather, allow oneself to be consumed by its disorder. “For years, I had thought that to write you needed, at the very least to master your subject,” Léger muses, “I didn’t know then that the subject is precisely what masters you.” This movement of being mastered by one’s subject comes to define Léger’s study as she stumbles upon a photograph of Virginia Oldoïni, The Countess of Castiglione, one of the most photographed women of the late-19th century. Little remained of her narrative beyond tales of her intoxicating beauty, stories of her affair with Emperor Napoleon III, and descriptions of her ferocious desire to be an object of attention. Léger’s Exposition moves beyond these narratives and puts forth a more compelling image of a life that swilled abjection.

Beautiful and enigmatic, the photographs Léger follow reveal a body of work at once incapable of being rendered and still emblematic: the Countesses’ body, overexposed and stubborn, drips with a desire to be seen, and yet what is revealed is far from a true portrait of the Countess herself. The idea of such a truthful portrait itself becomes elusive and, in turn, the Countess’ project of performance and craft is rendered legible. Through the rhetorical trick of self presentation, her excess and sincerity become pure articifice. The Countess is not a simple, passive subject photographed over 500 times; no, she had herself photographed to create, under the guise of superficiality, a portrait of impossibility.

It’s in this first book of her triptych that Léger gives us an initial glimpse of her mother. Through photographs, Léger relays her mother’s frailness, awkward sensitivity, her kindness. Her portrait though is incomplete and, just like the subjects of Léger’s books, her mother emerges alongside implied questions of intention and meaning: How could a woman allow such things to happen to her? Where was her defiant, unyielding voice? Why didn’t she speak up?

In the artfulness of Léger’s prose these questions float up next to reflexive questions of the writer’s own ability to ever fully understand another subject. As Léger herself notes, she did not always relate to her mother, a woman who seemed to have shrunk from the harm of having been abandoned, penniless with four children, no job, and power beyond reach. How could Léger, the writer whose work champions the female artist who railed against their framings, empathize with her mother, a subject who, to Léger, chose to be subjected to the whirl of the world instead of fighting against it? And yet, Léger does.

To be alienated by the female condition, bound to a subjecthood of lack, traumatized by the domestic, these are not unique, Léger’s mother notes. The form of these experiences, which Léger’s triptych confirms, radiates through history, space, and time. The suffocating interpolations of being a woman have concealed the words of so many: Pippa Becca, whose seemingly naive project is now bound to her rape and murder; American actor and director Barbara Loden, whose project of semi-autobiographical film Wanda details the listlessness of life for the 1970s American housewife; The Countess of Castiglione, whose hope had been to exhibit her photos at the upcoming 1900 International Exposition; and Léger’s own mother, whose words “too have been hidden away.” The triptych not only unearths the lost narratives of noted women; but more significantly the writers’ reckoning with her own mother — “I never helped her, I never stood up for her” — suggests that the triptych’s aim is to give voice to one woman: her mother.

Together, Exposition, Suite for Barbara Loden, and The White Dress craft a story part memoir, part fiction, part biography which surfaces individual narratives in the service of a much larger thought. To remember is also to look beyond the visible performance, to see those without stage, or camera, or art whose silence is the most significant expression of what it means to create.

FICTION & MEMOIR

Exposition, The White Dress, Suite for Barbara Loden

By Nathalie Léger

Dorothy Project

Published September 15st, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link