[ad_1]

Burning Worlds is Amy Brady’s monthly column dedicated to examining how contemporary literature interrogates issues of climate change, in partnership with Yale Climate Connections. Subscribe to her monthly newsletter to get “Burning Worlds” and other writing about art and climate change delivered straight to your inbox.

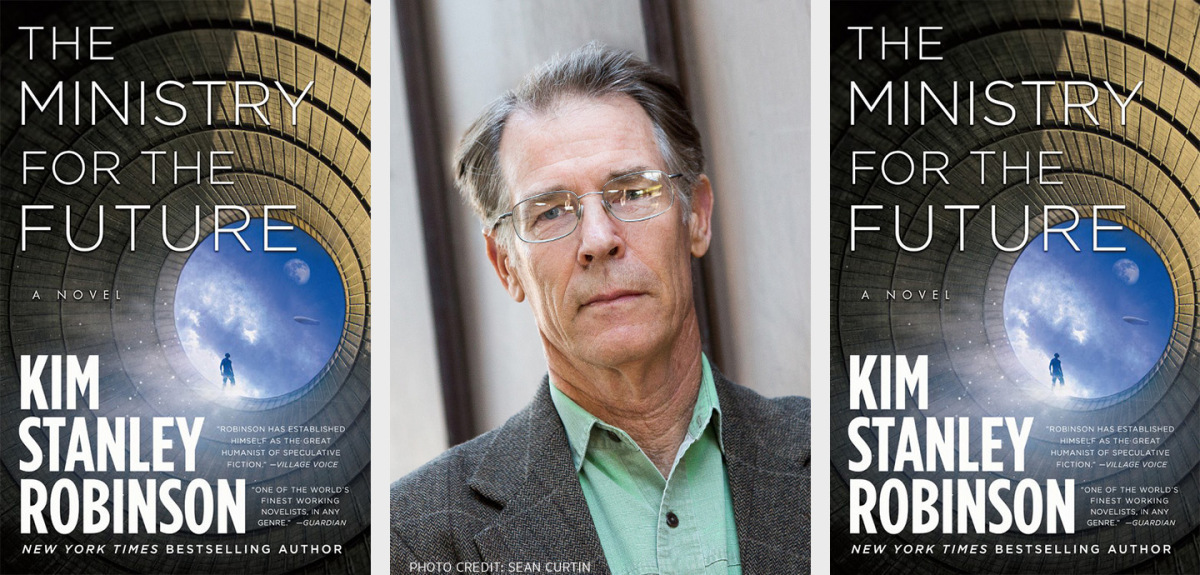

Called the “greatest political novelist” of our time by the New Yorker, Kim Stanley Robinson has infused his science fiction with real-life political, sociological, and ecological concerns for decades. He’s a writer who does his research. His work is often pegged as “hard” science-fiction for the level of detail with which he writes about social and technological advances. But he’s equally known for his optimism. His 2017 novel New York 2140 depicts a New York City half-submerged by rising seas, but by the story’s end, the city’s collective action suggests that a more just and sustainable future lies ahead.

Robinson returns with themes of climate change and hope in his latest, the tremendously engaging The Ministry for the Future. It opens in the very near-future with a gut-wrenching scene set in India during a heat-wave. From there, it follows several firsthand accounts of how the world’s political leaders and policy-makers worked together (or not) to take action on climate change by 2025. The book is rife with complex characters and clandestine government agents, but it also draws on real-life policies and economic theories to form a picture of a very possible future.

I spoke with Robinson about what inspired the book, his thoughts on the Paris Agreement and the United Nations, and why it’s hard to imagine the end of capitalism without ripping up civilization as we know it.

Amy Brady

You’ve written about climate change in your fiction before. What continues to draw you to this subject?

Kim Stanley Robinson

I’m a science fiction writer with a particular interest in the near future here on Earth, and over the next century or two on Earth and in the solar system. I like the solar system in the way I like Antarctica, it’s beautiful and interesting. But it has to be remembered that there is no Planet B, and Earth is our extended body, and thus a major character in all our novels, whether the novelists realize it or not.

So, we have already altered the climate and are in the first stages of a mass extinction event that we have started. That’s the reality of now, and science fiction (the strand I like most anyway) has always taken the present as the starting point for its speculations. So really I am stuck with it. No matter which future I imagine, climate change is part of it one way or another. I’m not saying there’s any inevitability involved here — the extent of the coming climate change is still up to us, and how we act now as a global civilization will make huge differences going forward. That seems to me to be the most important story of our time. And novels very often tend to try to tell the most important stories of any given time.

Amy Brady

The novel opens with a gut-wrenching scene set in India, which in the real world, is already imperiled by climate change. How did you arrive at the decision to open your book there? Were you inspired by real-life events or people?

Kim Stanley Robinson

Recent studies of the effect of heat and humidity combined have found that a temperature index of “wet-bulb 35” (which would be about 95 degrees Fahrenheit with 100% humidity, and then higher temperatures combined with slightly lower humidities, the curve can be calculated here), are fatal to humans who can’t take shelter in air-conditioned spaces. But in heat emergencies like this, power systems are likely to be overwhelmed and go down, at which point even people unclothed, in the shade, and fanning themselves, would still die, in a kind of slow parboiling that the body just can’t handle.

This can happen in many places, and these high temperature-and-humidity combinations have already been recorded and are happening more and more often, as studies of weather data have shown. One of the highest of these wet-bulb temperatures happened in the Chicago area in 1995. However, the main danger in this regard is in tropical and sub-tropical regions with dense populations and weak electrical grids. Many could be identified, but I wanted my novel to engage with India for a number of other reasons, and since the Gangetic plain is very much in danger in this regard, I decided to place my fictional incident there.

This was a very uncomfortable decision for me and I reached out for help from Indian acquaintances, and stuck with India in my story, and also described similar disasters happening in the Gulf Coat region of the United States, and so on. Even so, I remain terrified that something like this opening scene might happen in the coming decade. I’m hoping that among other things my novel might serve as a warning.

Amy Brady

One of the most fascinating aspects of your novel is its complex depiction of the United Nations. On the one hand, the UN is depicted as a catalyst for real, global change. But on the other hand, and without giving too much way, that change is only possible when leaders are willing to participate in clandestine activity that subverts a lot of aboveground decision-making. What inspired this plot line?

Kim Stanley Robinson

The Paris Agreement is a major event in world history and inspires great hope in me that it will serve as a framework for the world’s many nation-states to cooperate in decarbonizing rapidly enough to save civilization from all kinds of climate change damage and death. The Paris Agreement was brokered as part of a UN process and might be regarded as one of the greatest achievements of the UN so far, in a moment of extreme need for international cooperation and equity. Now, it’s true that it could later turn out to become something like the League of Nations—a good idea that failed, etc. But if we manage to deal successfully with climate change, it seems almost certain to me that the Paris Agreement will be part of the social armature of how we do it.

Even so, this effort will only succeed by defeating advocates of fossil fuel burning who will continue to fight to burn carbon into the atmosphere and profit from that. These fossil fuel advocates include some of the most powerful nations on Earth, and some of the most powerful people. They don’t see it like I do, or like the scientific community sees it, and they have enormous power in the political system, because money is power in our system, and really big concentrations of money exert a lot of political and practical power. That’s the reality of the situation we’re in — a biosphere emergency, a mass extinction event looming that will hammer humanity if it happens, and many very powerful humans fighting to make that bad future come to pass. Sad but true.

Given that situation, it’s going to be a fight. There’s the discursive battle, the fight for ideas that people support. There’s the legal battle, a fight for which laws rule. And there may also come physical material battles, a kind of loose ragged “war for the Earth.” It may happen. So a novel that just focuses on the diplomatic level, as if that will be the only one that matters, wouldn’t really be describing the situation accurately.

Sorry to say this. I’d prefer the good ideas to convince a working political majority, and then for the laws all over the world change to reflect that, by creating a new post-capitalist political economy that worked for all people and the whole biosphere in a way that gets continuously improved as we try things. Maybe that will happen.

Amy Brady

So many novels about climate change focus on the scientific revolutions that must occur in order to halt Earth’s warming. In Ministry For the Future, you focus equally if not more on the economic changes that must happen. Why is this?

Kim Stanley Robinson

Because this is the crux of the matter. The needed scientific advances have already occurred and are at hand ready to be built. There’s always room for improvement there, but if we only installed currently-existing technologies at speed, we could do a lot to solve the problems we have in living in balance with our biosphere’s processes.

So why don’t we? Because you wouldn’t make a profit from it. And in our current global political economy, sometimes called neoliberal capitalism, we only do what is defined to be profitable. So capital won’t be invested in the necessary work, and we are doomed — unless we quickly invent and install a new political economy in which we pay ourselves to do the work to build a decarbonizing infrastructure, along with many other needed tasks that are not profitable in the current dispensation.

Saying this is easy and to me even obvious, but then, thinking about describing a future where good things happen, that inevitably led me (again) to writing about finance, in this case mainly the central banks, both national and international. If another big round of quantitative easing got started by the biggest central banks working together, and the first spending of that newly created money get dedicated to decarbonizing work, that might be a good start from within the system that we are currently stuck in and have to work with, at least for now. Thus my plot.

Amy Brady

A character in your book laments how hard it is for people to imagine the end of capitalism. That certainly feels true in the real world. Why do you think humans can more easily imagine, say, enormous leaps forward in technology, than capitalism’s end?

Kim Stanley Robinson

I’m not so sure about this. I know it’s fashionable to say so, but I think it’s actually quite easy to imagine capitalism ending — by way of apocalyptic catastrophes, mass chaos and disorder, the collapse of civilization, and the beginning of a war of all against all. Dystopian literature, post-apocalyptic literature, these are all various ways of imagining capitalism’s end.

Of course, that’s not what people mean when they say that. It’s not that alternatives to capitalism are hard to imagine — you can write out a just and sustainable world constitution in half a day. And you can imagine civilization collapsing in a single bad dream. Now, in the middle of the current pandemic, and a really intense election and hopefully a change of administration, it’s easier than ever to imagine a collapse. What’s hard, I think, is imagining how we could get from our current situation into a better situation. People recognize that capitalism as world system blocks that transition, and given how entrenched it looks, it seems like there’s no realistic way forward, no bridge from our bad place over the next few decades to a better place.

In this situation, it’s important to remember that fossil fuels advocates and most of the power elite — the one percent, or even the richest ten percent — want this system to look entrenched and impossible to change. That helps them hold onto power and privilege for the rest of their lives, and after that, they don’t really care. This is my guess. So it’s important to resist that impression. In fact, the current order is unsustainable, and what can’t happen won’t happen, so some kind of change is for sure coming. Things could get worse, sure, but it’s also still true that things could get better. And that’s what we need to work on.

Amy Brady

I love the structure of this book. Would you discuss why you chose to write from so many points of view?

Kim Stanley Robinson

Thanks for that. Given its subject matter, the book’s structure was my special pleasure too, and I hope will be part of the fun of reading it. Because art is for fun, and fun can teach — see Aristotle on this, or Brecht. I really enjoyed that part of the work on this one.

So, I wanted to tell a global story spanning a few decades. The usual structure of the novel (which I love) didn’t really suit that desire. But I was encouraged to try something different and appropriate to the topic by my wonderful editor Tim Holman, who had some excellent suggestions for how I might proceed. And I have a lot of faith in the novel as a really capacious form. And I like formal experiments in novel structure as a reader, and have tried quite a few of them as a writer. The novel is often polyvocal, a heteroglossia as some have called it.

So for this one, I decided I would anchor the story in Zurich, and in the lives of Mary and Frank and a small circle of secondary characters around them, mainly Badim and Tatiana, and then give over the rest of the novel to eyewitness accounts, which I discovered is really a separate genre with its own norms, which turned out to be incredibly useful to me for this job. That discovery was my favorite part. Then a few other modes as well, including the 18th century’s “IT” narratives, and riddles out of old English, and meeting notes, radio show transcripts, and so on. I’m aware the result is kind of cumbersome and strange, but oh well. I tried to keep it quick too, and form follows function, so you do what you have to. And when I found the form for this particular function, it all came together for me.

Amy Brady

Despite depicting catastrophic events, The Ministry for the Future — like many of your climate-themed novels — isn’t without hope. Would you say that you, personally, are hopeful for the future?

Kim Stanley Robinson

I think hope is a moral obligation, so I try to stay hopeful. That said, the situation we’re in is radically dangerous. We’re entering a decade of intense conflicts all across the board. In a situation like that you end up saying things like, “Wow, I hope civilization survives.” That’s still hope, right? And beyond that, it’s worth saying, if we succeed in inventing and installing a global post-capitalist world order focused on justice and long-term sustainability, results could be really good, really exciting. I think that’s still true, so despite the conflicted years we’re entering now, that thought gives me hope. We’re a cooperative species in many fundamental ways. Mutual aid is standard among us as social primates, and social reproduction is always going on below all the weak economics and the power politics. So I say, be hopeful, keep your eyes on the prize, and put your shoulder to the wheel.

FICTION

The Ministry for the Future

By Kim Stanley Robinson

Orbit

Published October 6, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link