[ad_1]

It’s hard to sum up Marie NDiaye’s That Time of Year (Un temps de saison, translated from French by Jordan Stump), a short novel that unfolds with a dreamlike logic. Every year Herman, a math teacher from Paris, spends the month of August with his wife Rose and their son in a small country town where it is always warm and sunny; but, this year, when the family lingers into the month of September, the weather changes abruptly to cold rain. Rose and the child, who have gone out to buy eggs from a local farmhouse, never return. When Herman goes to the village to report their disappearance, he is met with unfailing politeness and complete indifference from the police and local government.

NDiaye is a prolific French novelist and playwright. The daughter of a French mother and Senegalese father who grew up in France but now resides in Berlin, she explores throughout her work questions of exile, disjuncture, and belonging, often in fantastic and narratively disjointed ways. Her most well known novels include Three Powerful Women and Ladivine. Un temps de saison appeared originally in 1994 and was her fourth book. Like most of her work available in English, it has been translated by Jordan Stump, a French professor at the University of Nebraska, who for some time has been turning out eloquent translations of contemporary French writers such as Eric Chevillard and Patrick Modiano. That Time of Year appears thanks to Two Lines Press, which has also published NDiaye’s My Heart Hemmed In, Self-Portrait in Green, and All My Friends, also translated by Stump.

In That Time of Year, NDiaye dispenses information to the reader in a matter-of-fact tone that belies the unusual circumstances of the world in which the novel takes place. The women in this town all wear the same kind of blouse, tied with ribbons that indicate whether or not they are married. When Herman takes a room at a local hotel, he is told to leave the door unlocked at all times. Eerily, an old woman watches him continuously through the window across from his room. The president of the local chamber of commerce becomes Herman’s unlikely ally, confiding in him that the only way he will ever see his family again is if he stays in the village, forgets his former identity, and becomes a villager himself:

“Forget everything that attaches you to the life you led here as a Parisian vacationer. Watch what you say. And you’ll find that, little by little, without your even knowing it’s happening, you’ll be led to your wife and child, and then, who knows, then maybe you won’t be too happy.”

What at first appears to be a Kafkaesque fable about insiders and outsiders quickly morphs into a metaphysical horror story about the bonds between the living and the dead. As with Kafka, there is a sense of an allegory that cannot be pinned down, a multiplicity of meanings that resonate in such a way that interpreting the text is like trying to make sense of a nightmare.

Not surprisingly perhaps, That Time of Year ends abruptly, in a manner that is open-ended yet somehow just right. This is the kind of book that will frustrate a certain type of reader and delight others, especially those with a bent for the innovative and indeterminate. The novel shares some DNA with the Argentinian writer Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream in its embrace of the fantastic and as a haunting reinvention of the literary horror story. As a small taste of NDiaye’s work, it left me eager to read more—and thankfully, there is much more of her work to be found.

FICTION

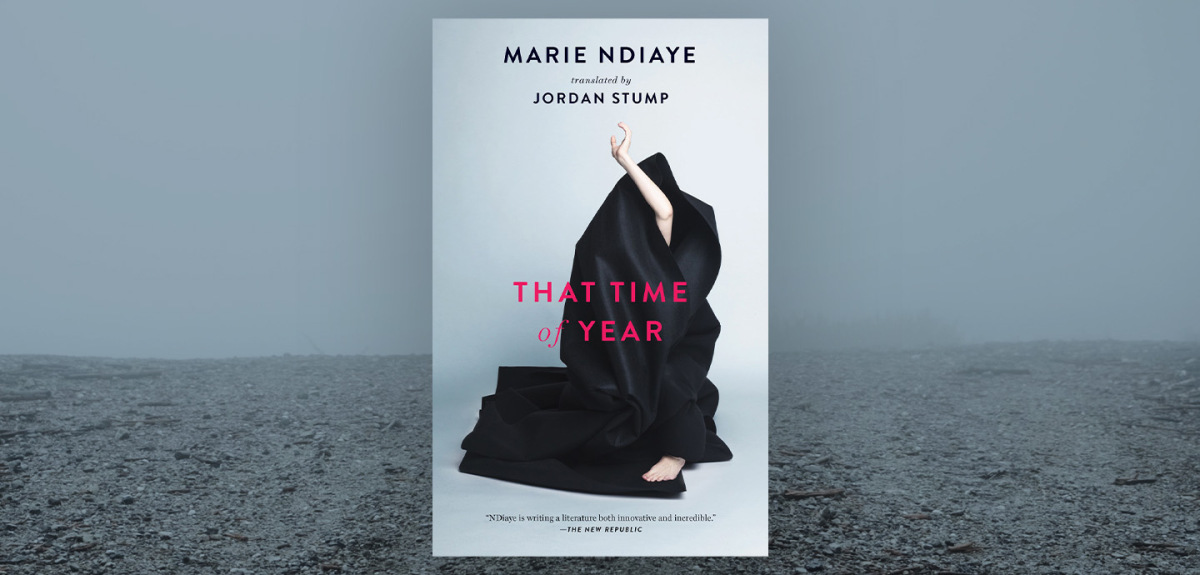

That Time of Year

By Marie Ndiaye

Two Lines Press

Published September 08, 2020

[ad_2]

Source link