[ad_1]

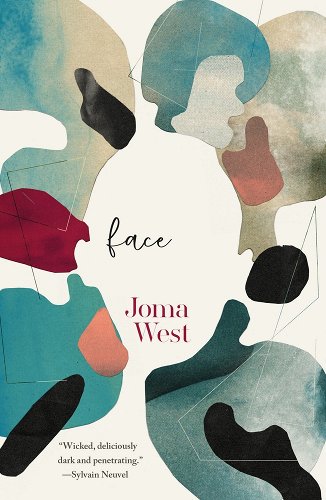

The world of Joma West’s debut novel, Face, is one where people can design an unborn baby that someone else delivers. Physical touch has been rendered obsolete. Individuals called menials are “programmed” to serve other people without question. Romantic relationships have evolved into transactional partnerships between people based on personal gain. What’s most compelling about West’s futuristic setting is the omnipresent, augmented reality that allows people to interact like characters in The Sims video games (no need for an external device) or The Matrix film (after the red pill unveils the truth about free will). People can “jack in” and begin moving through a digitally engineered world utilizing an equally engineered persona. West seems interested in the interplay between how people are affected by real people in the real world (or the On) and the virtual world (or the In). No matter how connected everyone is to everything given the advancement of technology, there are still limitations that can prove to be detrimental to people’s humanity.

The concept of “face,” in its simplest explanation, represents social value. People modify their face in the real world and the digital world to navigate each space as if in a kind of caste system—working hard to maintain or improve status. Everything from eye color to personality can be curated into personas (often multiple) that function as social media avatars for the real world, where everyone is jockeying for position, especially West’s cadre of characters.

The novel begins from the perspective of a menial, Jake, who gave himself this name, which is not part of his initial programming. Menials are humans that are bred to have no feelings or desires, so their servitude can be written off as more “humane,” despite being sold and distributed from a warehouse with the threat of termination if they begin to “malfunction” before their predetermined shelf life. Jake’s glitch is emotional. He wishes to be more human and therefore have a name. We also learn that he has a strong romantic desire for one of his owners, Madeleine, and a growing violent desire toward her coupling partner, Schuyler. There is little that separates Jake from a “real” human, given the fact that he is malfunctioning, and true emotions are seeping out into his everyday existence. Watching him work through his feelings via the relationship with the family he serves and his confessional sessions, a novelty for menials, is an allegory for the decaying relationship people have with each other and the growing dependence on technology to the detriment of society’s well-being.

The next storyline follows Tonia and her coupling partner, Eduardo, as they grapple with the decision to “have” a child. The aforementioned Schuyler, their associate, is a high-level socialite with cachet that makes his word as good as gold. When he suggests Eduardo and Tonia see the best in the child-design profession to discuss their future, the first crack in the relationship façade becomes apparent. Tonia isn’t sure that she actually wants to raise a child, but when she goes into the program to design her child, she chooses eyes, skin, and features that result in her looking at a version of herself that she can’t deny.

Meanwhile, Schuyler appears to be coming apart at the seams, with Madeleine falling further out of his favor and his two daughters, Reyna and Naomi, having some realizations of their own about the importance of authentic humanness. Reyna’s identity crisis is puzzling to Schuyler as he felt she was perfect and capable of harboring his secrets. Naomi, who is not as good at playing the face game as everyone else, begins exploring the menial industry to determine the degree to which humanity’s integrity has eroded.

At once, West is making a parallel argument: that despite the advent of new technology that has greatly overtaken culture and society, humanity is just beneath the surface, pressing upon the thin membrane, threatening to break through. In a world where authentic humanness is looked down upon—so much so that people use drugs to block everyday emotions—it means something that Reyna must resort to the beta blockers so frequently. Naomi, a teenager who shrugs at most aspects of life, finds herself compelled to investigate menials, wishing they were allowed to feel the very same emotions her sister regularly suppresses.

Lastly, Face is a biting look at the dangers of where society places its value. Personal identifiers such as race and class are superseded by an individual’s online profile. West’s book is prescient when content shared on a social media page, if noticed by certain parties (e.g. employers), can derail one’s future, and when a viral post can earn someone a partnership worth millions of dollars simply because of the number of followers they have. West has been to the future and returned to write a book so powerful it might be the message in a bottle that will save society. Would that we were to log off long enough to remember how to process our feelings and maintain relationships—engage in what makes us human—before the uncanny valley fades away as technology continues to advance.

FICTION

Face

By Joma West

Tordotcom

Published August 2, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link