[ad_1]

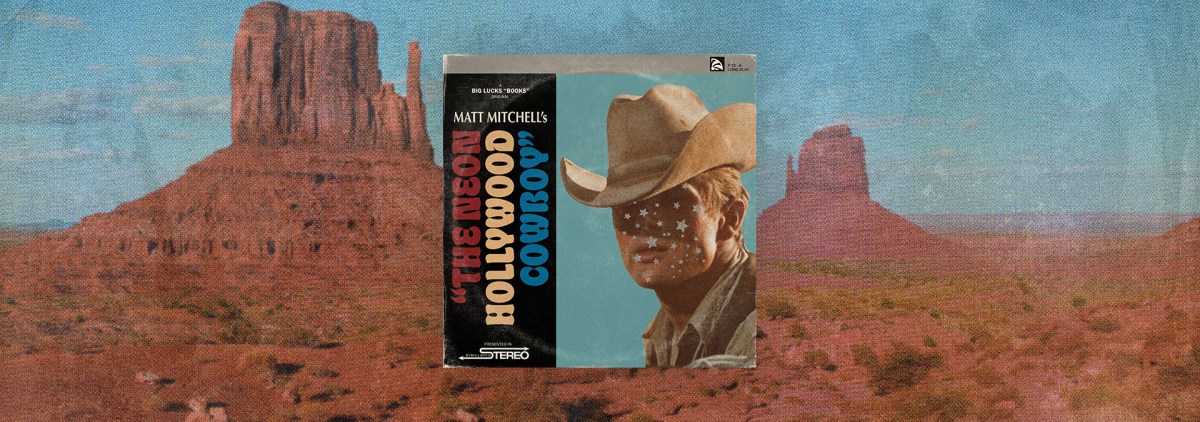

Matt Mitchell’s debut collection of poetry, The Neon Hollywood Cowboy, examines identity through the eyes of its eponymous archetype, depicting a nomadic traveler, saddled to his horseback, slipstreaming every passing moment into another literary confessional. The Neon Hollywood Cowboy represents an alter ego for Mitchell to funnel his own story through. An alter ego channeling the strength of self-admission within every line break.

Every moment inscribes another deep cut from the past but also acts as an echo chamber to the present. Such deep cuts can be found in the poem, “Pat Benatar Soundtrack My Gender Dysphoria,” Mitchell writes:

“my mother wanted a daughter so badly

she got one

with a face painted like every single boy

who ever hurt her.

if my rib is a man’s rib, but I have never seen it,

how can I be sure?”

Mitchell offers a glimpse of his own upbringing: a self-imposed questionnaire on gender identity. How do we define our bodies? Do such labels serve any real purpose? It should be stated, Mitchell is referring to the internal and external stigmas accompanying Intersexuality, the existentialism of living in a body composing two different genders.

What also makes the theme of identity a vital component of the work is how it affects the narrative’s ever-changing dynamic. Although The Neon Hollywood Cowboy is an aura prevalent in every poem, there are two other crucial archetypal figures who shuffle into the narrative: Mitchell himself and any cultural iconoclast he chooses. For the latter, “River Phoenix is Running on Empty” reminds readers there are other voices telling this story for him, through their own reimagined endings. The poem expands on the thought of Mitchell’s own gender identity to encompass a more universal paradigm on identity itself. This is first referred to in the dedication line at the beginning of the book:

“for James & River

for bodies not yet grown into”

A first look at the two-line memorandum might allude readers’ thoughts to purely elegiac language. However, those who know of River Phoenix probably know he passed away at the age of twenty three from an overdose at the peak of a legendary acting career. Yet, there’s no sole tribute to River, but instead a more generalized commentary for all who failed to realize their own being before it was too late. A commentary on the “what could’ve been” moments for those we all mourn.

Despite the “taken from this earth too soon” rhetoric, complex takes on one’s identity are revelations without a chronological checkpoint. This only proves Mitchell’s point that not everyone has all the time in the world to love and embrace oneself, nor a ticking clock for knowing the body they might grow into. For some, it can take until one’s teen years, and for others, it can take a lifetime. With River, we may never know, and “River Phoenix is Running on Empty” does an excellent job making such an argument:

“like birthday cake chandeliers.

or river phoenix in running on empty

evading the arms of the fbi,

and me thinking the fbi should have just succumbed

to the soft animals of their bodies and kissed instead.”

Mitchell’s subtle display of identity reminds society of all the passions it buries, all the lies stirring our insecurities, and all the missed opportunities when it comes to embracing who we really are.

When I read Mitchell’s work, I’m reminded of the foreword written by Hanif Abdurraqib. In one important line, Abdurraqib compares the work, what went into it, and the process behind the making of concept albums:

“The poet also has to wrestle with that same balancing act, but there are maybe more tricks at our disposal to fall into some simplistic signposting about how a story is living, or where the story is going next.”

Hanif’s commentary touches on such an important part of Mitchell’s poetics. Mitchell’s work refuses to fall into that trap of pitfall clichés and cringeworthy “precious moment” tropes. Instead, he lays his words out on an open plain for all to see with uniquely evocative imagery and a truly experimental narrative that moves fast without losing any of its meaning.

The Neon Hollywood Cowboy isn’t just a contemporary Western epic, a love letter to the universe, a pop-culture Necronomicon, or a seventy-five plus page anthem; it is undefinable and that’s what makes it an absolute masterpiece. I realize the word “masterpiece,” like many bold entitlements, gets thrown around like confetti and cheap glitter. However, Mitchell’s theme of identity packs itself into a category all its own. There is no formula, no canon to obey, no ancient meter to adhere to—just a young poet, who has lived a thousand lifetimes in two bodies longing to know if they’ll ever be seen, and not just heard. Mitchell is not afraid to invite readers into this cathartic dreamscape, detailing both his struggle and his triumph. A literary masterpiece at its core is one that stands out in the face of its predecessors, and its contemporaries: The Neon Hollywood Cowboy achieves just that.

POETRY

by Matt Mitchell

Big Lucks

Published on May 1, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link