[ad_1]

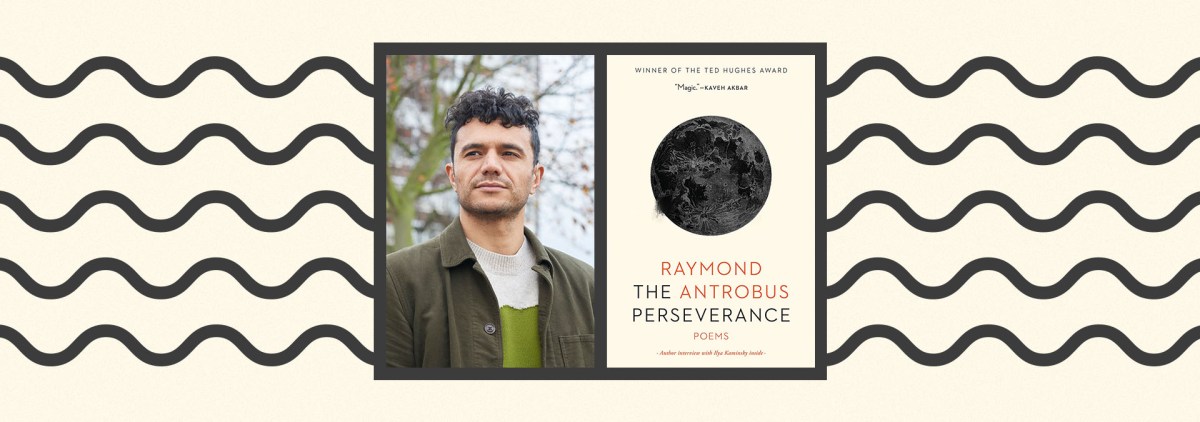

The title of Raymond Antrobus’s debut collection, The Perseverance, derives from the name of the London pub the poet’s father used to frequent, an establishment whose doors were shut upon young Raymond, with “50 p. to make [him] disappear,” many an afternoon. Deaf from birth, the boy would stand in front of this everyday port of entry—one more concrete symbol of the adult-hearing world and its denial of access—and slip into reverie.

Decades later, the adult Antrobus pulls this warp in time’s fabric inside out: instead of seeing himself as one who must linger in front of forbidden portals, he now boldly invites himself and, fortunately, his readers into his own private territories. Housing us in a tender, elegant, and sometimes brutal language, his “noiseless palace” becomes our palace of sound/unsound and occasional fury, one exceptional in its musically enlightened architecture.

The Perseverance has won the Ted Hughes Award, the Rathbones Poetry Prize, and the Somerset Maugham Award, and was shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize, among others. I recently interviewed Raymond Antrobus about his outstanding collection.

Ryan Asmussen

For me, one of the major themes of The Perseverance is how different types of language, traditional and nontraditional, create or destroy types of human connection. Of course, this is largely introduced via your experiences with British Sign Language, but there are other languages you speak in these poems, as well. Emotional, socio-cultural, racial. As a poet, how conscious would you say you are of language as an attempt to narrow the meaning gap, as it were?

Raymond Antrobus

That’s such a good reading of the book. Yes, absolutely, I was thinking a lot about the hierarchy of language and how that plays out sociologically. I thought about the exclusion of sign language and my own embarrassment and shame as a kid who had learned some of it and how self-conscious I was about everything to do with language. How I spoke, signed, wrote—all these things, as you say, had racial and class implications which again, I wouldn’t understand fully until becoming a teacher, because I then got to see how all these things play out from a distance. I saw how a kid can have a “working-class” way of speaking and signing and how he may be picked on by the more middle-class kids and vice versa. Your idea of language creating and destroying connection is profound. I’m going to ponder that.

Ryan Asmussen

The semantic fields of these poems run wide, often bending in various directions even within the space of a single poem. I know this can be a tricky tightrope walk in the writing. How do you know when a poem ‘doing different voices’ like this hits the poetic mark for you, instead of sounding, say, disjointed, unconnected?

Raymond Antrobus

Yes, that’s tricky, and truthfully, I don’t know. I’m guided by what I read and that feeds into my writing instinct. I’m always trying to serve the gut feeling that pulled me down to write a poem, it’s important not to lose track of that. I’ve had editors offer something “better” or “more surprising/off center,” and I’ve not taken those suggestions because they haven’t served the vague reason I might have for the function of the poem. Does that make sense? This is where experimenting with form was particularly useful.

Ryan Asmussen

A persistent intertextuality also stands out. There are poems speaking to other poet’s poems, most notably to Ted Hughes’ “Deaf School.” The Hughes speaker finds the children empty of self, automatic, like machines. They lack “dimension;” their bodies are “removed / From the vibration of air.” Not only do you eloquently refute this, but you also affirm, as I see it, the positive opposite: that, in fact, the D/deaf are more attuned to this vibration of air—in their sensitiveness to the nuances of mind and body as well as to the societies around them. Would you agree?

Raymond Antrobus

Of course! Hughes could have been talking about me at school and, yes, Hughes’s work made an impact on me. I loved his book The Iron Man as a kid and I loved “The Hawk in the Rain” and “Crow,” in particular. I never studied poetry or writing formally, so these were books I read for pleasure. When I found his poem “Deaf School” it was such a violent offence to me. One of England’s most revered poets being capable of such arrogant narrowness that, after that, it changed the taste of all his work for me. He started to sound too certain of himself at the center of the universe, and that’s why I had to respond using the poetic device Hughes seemed to use the most (a nature-based extended metaphor). I found myself in New Orleans by the Mississippi River and thought, why not respond as the river? Last week, I gave a reading to my old school in London (D/deaf school) and getting to share stories and poems with some mutual understanding of deafness makes me think that I’ve completely revised the poem and brought that revisionist practice to life. Having said that, no one is perfect. I don’t think Hughes meant maliciousness, he was just ignorant, and I try to be compassionate to that too. My guess is Hughes never actually spoke with a Deaf person or learned anything about sign language.

Ryan Asmussen

Ironically, this collection garnered you the prestigious Ted Hughes Award. Do you have any pleasant connections to his work? Are you an ongoing reader of his?

Raymond Antrobus

Yeah, that was complicated. I thought it was a joke. I went from risking a lawsuit from the Ted Hughes estate to winning the Ted Hughes award. LOL. The irony isn’t lost on me. I can’t deny Ted Hughes’s contribution to English language literature, and I find it more interesting to engage with complicated people and their work. There’s a sense that people are constantly seeking purity, a kind of unproblematic greatness and I’m not sure that it exists. Whoever we give our love and admiration to has the potential to break our hearts and let us down with their shortcomings but perhaps that’s just us not having a mature or brave enough idea of love and admiration? I don’t know. In short, yes, I do still engage with Ted Hughes.

Ryan Asmussen

As a record of one Deaf man’s experience of moving through the noise and song of life, these poems offer a hearing reader remarkable insight into your experience. One can try and extract from one’s own muffled or soundless moments what deafness must be like, but, of course, one can’t even come close. How much of your efforts in this vein are a kind of education-via-poetry for the hearing? I know, for my own part, there were instances in my reading where I found myself caught short and breathless when you brought a particularly striking image, juxtaposition, or figuration about your world into play.

Raymond Antrobus

That’s interesting to know. Truthfully, I had no conscious interest in “educating” a hearing audience. My allegiance was to whatever felt like truth or as close as I could get to it. I’m glad the work engaged you in such a way! That’s a gift for a writer to know.

Ryan Asmussen

Your father is a vital presence in these pages. At first, a reader may draw certain understandable conclusions about his character, but these are overturned as more layers of his complexity are revealed. Was there a private unwrapping process you had to undergo in the writing? Did you discover more of him in each poem?

Raymond Antrobus

It was tough. I had to deal with each poem as its own idea, memory, and language. People are complicated, our families are complicated. It was only after becoming a teacher and having access to the lives of so many other families that I realized how uncommon my upbringing was. Yet I’m incredibly grateful for my childhood and to my parents. They did the best they could with what they had.

Ryan Asmussen

You generously acknowledge the help and inspiration of several contemporary poets in this collection, as well as in interviews. Are there any twentieth-century poets (or even earlier ones) who, you now discover, have offered you an especial path into your own voice?

Raymond Antrobus

Yes, far too many to mention them all, but off the top of my head: William Blake, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Coleridge, Lorca, Emily Dickinson, Claude McKay. I’d come across a deaf English poet and preacher called “John Kitto” who wrote sonnets. It turns out he lived in the same area where I went to university to study teaching. I still dip into his work and feel a kind of kinship with it.

Ryan Asmussen

In “Dear Hearing World,” you write “I have left Earth in search of an audible God. / I do not trust the sound of yours.” As I see it, the poetic act is one in which the poet temporarily leaves her earthbound-ness to see, imaginatively, this earth—perhaps merely but singularly her earth—more clearly and to give utterance in a most searching way to an aspect of its profundity. Do you have any thoughts as to how your personal act of composition, your moments of communion at the desk, may be different than a hearing poet’s? I realize this may be a strange or even unfair question. I’m thinking of states of artistic consciousness.

Raymond Antrobus

Hmm, I don’t know because I’m not a “hearing poet,” the poems in The Perseverance are, however, engaging with both the hearing and Deaf world. Both have their own mythologies, and I don’t completely subscribe to either of them. My quest in the book is language, connection, family, education, grief—all the earthly and ethereal things to do with how one might stay tethered to the living.

Ryan Asmussen

In what direction do you see your work moving, on any level? Can you envision a near-future time when a particular subject or technique envelops you? Where might your inevitable development take you?

Raymond Antrobus

I’m not sure. I’ve written another book of poems, out later in the year, and those poems are quite different, despite some similar territory. A big difference in terms of process is giving live readings, which has been intrinsic to my process, and I’ve lost that to lockdown. I know that’s changed the feeling of the poems I’m writing and have written now. Not necessarily for the better or the worse, just different. I’m also engaging in more visual art these days. The work of Frank Bowling, Christine Sun Kim, Noah Davis, Phoebe Boswell, Othello De’Souza-Hartley, Saul Leiter, just to name a few who have inspired me. My wife is an art conservator, so she’s always introducing me to stuff too. I don’t know yet how this is going to impact what I write, I guess we’ll have to see.

POETRY

The Perseverance

By Raymond Antrobus

Tin House Books

Published March 30, 2021

[ad_2]

Source link