[ad_1]

The phrase “conservative critic of US foreign policy” generally has a particular connotation. One imagines a sweaty call for even more bombs, more spending, more muscle against every enemy real and imagined. It is assumed the more force the better, no matter the outcome.

That’s not the style of Andrew Bacevich, a long-time critic of the US foreign policy consensus. Bacevich, a retired colonel in the Armor Branch of the United States Army, is a prolific writer, a self-described “Catholic conservative,” a Vietnam veteran, and someone who believes that there is an inherent dumbness in the way America conducts its wars—a dumbness that springs from a messianic and blinkered belief in its own greatness.

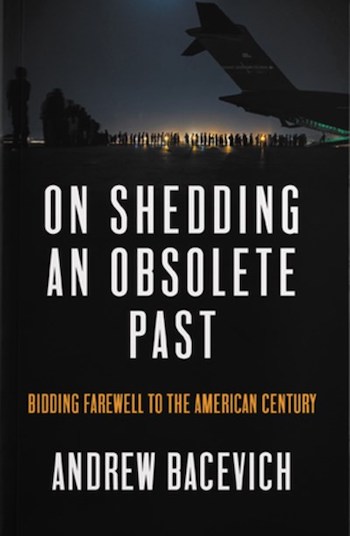

Bacevich has a new collection of essays originally published in TomDispatch, a stubbornly idiosyncratic vestige of a better internet. The collection, titled On Shedding an Obsolete Past, looks at the Trump and early Biden years, and analyzes the present by drawing a throughline from the 20th century, from Wilson straight through to Biden, with the main focus being on the Trump administration.

Now, many readers are perhaps salivating at the thought of takedown after takedown of that venal buffoon, and Bacevich’s contempt for Trump is not exactly hidden. But Trump is not the target or at least not Trump as Trump. Instead, the primary target is what Bacevich calls “the Church of America the Redeemer.”

America the Redeemer has broad bipartisan consensus—taking into account a few broken eggs, America overthrew tyranny, Lincoln freed the slaves and was martyred, and in the 20th century the US defeated the twin evils of the world, Nazism and Communism. America, the belief is, is a nation dedicated to freedom. Where it has, you know, slipped up and installed tyrants (i.e. every continent, every decade, every year) is a failure of promise, not a pattern. Or, as Bacevich, both damning and disarming while describing the Church says, “When it comes to shalts and shalt nots, it tends to be flexible, if not altogether squishy.”

Bacevich rightly skewers this belief and those who hold it (David Brooks, that ninny, is the first main target). But Bacevich is not interested in a litany of obvious sins. He is more interested in the divide between the Blob (the foreign policy consensus) and its failure to deliver, with all the attendant gloom and disassociation that has brought. It’s less a critique of policy as it is a dissection of what that has rendered: a nation that is flailing, that has no center, and that is filled with broken promises.

That, in one argument, has helped lead to Trump. Bacevich of course dismisses Trump’s claim to Everyman status. But he also argues that for certain people, the triumphant promise of the post-Cold War, with America as a sole chest-beating power, the sole survivor at the end of history, didn’t pan out. Failed wars, economic disasters, rising inequality, a sense that things weren’t going to get better—is this victory? As Bacevich says, “my sense is many Americans have an inkling that history of late has played them for suckers.”

It’s an odd notion—failure—and one that America doesn’t particularly enjoy. We tend to ignore the bad and focus on the good, even while the bad comes grabbling out of the ground. Given the role of the Church of America the Redeemer, this leads to a striking disconnect. A militantly optimistic and unquestioningly militant leadership class crowing about freedom, and then the rest of us.

One of the most striking images takes place in the small Illinois river town of Marseilles, and don’t pronounce it the French way, hear? This is where there is a monument to the “Middle East wars,” a vague lumping together of Afghanistan and Iraq. Here, in this economically-battered town halfway from nowhere, is where the disconnect between high rhetoric and human lives was starkly clear.

“Although my son’s name is halfway down near the left margin of Panel 5B, I find myself uneasy with any reference to American soldiers having died for freedom in the Greater Middle East. Our pronounced penchant for using that term in connection with virtually any American military activity strikes me as a dodge. It serves as an excuse for not thinking too deeply about the commitments, policies, and decisions that led to all those names being etched in stone, with more to come next month and probably for many years thereafter.”

It’s clear that this passage is personal for a father, a soldier, and an American. Bacevich is less interested in exploring the hypocrisy as he is in examining the waste. The squandering of resources and blood. The hollowing of America while we pretend to be something we’re not. The sense that we’ve failed a generation clinging to an obsolete idea, and that failure is tearing us apart. In that, his true conservative nature comes out: why do something stupid, he asks, when we can just not do that?

If there is a problem with this collection, it is that while Bacevich sees Trump as a response to these failures, he also sees him as an extension of the Blob—a crude one, a dumb one, and absolutely incompetent one, and maybe even an unwitting one, but a standard US President at the end of the day. That’s not entirely wrong, on the surface, and Bacevich is right that Trump didn’t create America’s divisions. But it misses something essential.

The vast black hole of Trump’s venality, his greed, his endless need for creating enemies, and most important his absolute lack of loyalty to anything but himself freed the American right from the obsolete past. They are no longer interested in American greatness as a messianic project, but as a tool for punishing the enemy—namely, anyone who isn’t a white Christian. They have linked up with the international far right in deed and action and shared enemies. Trump didn’t create this but his towering emptiness created a clean break with the past. Trump’s followers are the heirs of an alternative universe, where America Firsters beat Roosevelt and America sided with the Nazis, via arms or shrugging indifference.

This is not the kind of break for which Bacevich was calling. In a way, he was rightfully focused on the idiocy of the Church and didn’t see the sins of the schismatics. Neither path is the way forward. It’s up to us to decide how to fight both the near enemy and the enabler. Only by defeating fascism, and recreating the American ideal, can we finally be done with both horrible universes.

NONFICTION

by Andrew Bacevich

Haymarket Books

Published on November 15, 2022

[ad_2]

Source link