[ad_1]

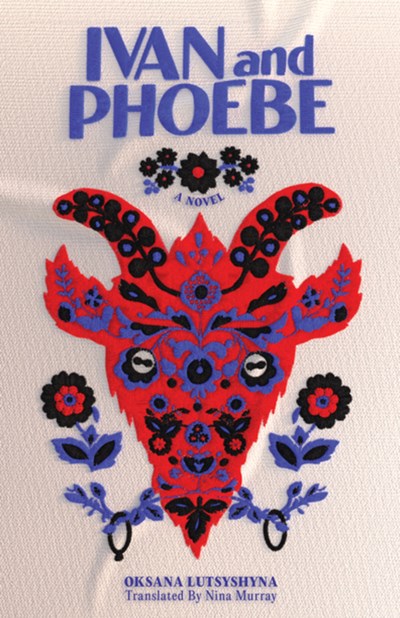

Some readers may think of Oksana Lutsyshyna’s award-winning novel Ivan and Phoebe, translated from the Ukrainian by Nina Murray, as “supplementary reading” to better understand Russia’s current war against Ukraine. And it could serve in that capacity: the rich contextual detail Lutsyshyna provides creates a fascinating relief map of Ukraine’s complex past, and the story includes real historical figures and events. It centers around fictional university student Ivan’s participation in the Revolution on Granite, a student-led protest in Kyiv’s Independence Square in October of 1990. The protest grew to a massive scale and forced unprecedented concessions from the Soviet government, ultimately contributing to Ukrainian independence from the USSR the following year.

But Lutsyshyna’s approach offers much more than a contemporary’s closeup view of the seismic shuddering of Ukrainian social and political institutions. Rather, she illustrates the weight that institutions everywhere have on us, creating a universal dimension to the story that makes ample space for every reader.

Having recently completed university in Lviv, Ivan returns to his hometown of Uzhgorod, a small city in western Ukraine, eager to leave the Revolution—and the government informant menacing him—behind. He moves back into his parents’ home and reunites with childhood friends, but he still struggles to adapt. Though he heroically stood with his fellow students in Kyiv, facing down the police and publicly taking a stand against the Soviet government, his status as an “ex-revolutionary” and the baggage that it entails leaves him at loose ends: “Nothing spurred him to anything, nothing urged him, nothing compelled him—he was forever being tossed to the very bottom of life, the only place where he seemed capable of surviving.” Though he begins a romance with his boss’s daughter and eventually marries her, he still drifts, alienated and ambivalent. In order to find his place in the new society that he fought for, Ivan must find a way to live—with his past, with his family, and with himself.

Alongside the large-scale sociopolitical tensions that sculpt the narrative, Lutsyshyna also captures in fine detail the tensions within and among the characters. She pivots easily among their perspectives, peering into their psyches to report more than critique. Of Ivan’s brash, overbearing brother-in-law, she dispatches:

Styopa’s was the most superior reality—one you could touch. All these money transfers and the stupid internet were, for him, at best, marginally helpful in life, but they were not life: life was a field of potatoes to be harvested in the fall, animals raised for food, cucumbers in the greenhouse, and the house—the impregnable fortress a man could rely on in times of mortal danger. And the times—they would not be long in coming. Styopa had no need to read philosophy and no reason to believe any end-of-the-world doctrines. The end of potatoes was for him the end of the world, and the end of bricks—the end of history.

This type of evenhanded but penetrating omniscience when applied across characters allows us to see a web of stress fractures inflicted by the institutions that they live among and within. This applies to political institutions, to be sure. Ivan’s experiences with government have left him traumatized and disaffected, and he isn’t alone in that. Even Sashko Petrenko, the government informant who pursues and torments Ivan, inadvertently reveals the disjuncture between who is he and the institution he serves:

The smile vanished from ‘Sashko’s’ face. In fact, for what had to have been the first time in their entire acquaintance, his face reflected a spontaneous emotion, a whole cocktail of uncontrolled feeling: anger, shame, and something else, something hard to describe—Ivan grasped it on a cellular level: he recognized, to his astonishment, that ‘Sashko’, despite everything, wanted to remain in his, Ivan’s eyes, a good person.

But it’s not just matters of state. In Ivan and Phoebe, the institution of marriage warps or even shatters its participants, leaving them unrecognizable to themselves. Ivan conceals his wife Phoebe’s cherished poetry: “…for whatever reason, he hadn’t been able to make himself return [it] to her. He did not know why.”

As for Phoebe, she is afforded the singular opportunity in the book to speak for herself—something she struggles to do in her life, pinned as she is under the social structures heaved on top of her. In two anguished stream of consciousness-style monologues she paints a brutal picture of the devastating effects that womanhood—and particularly marriage and motherhood—have had on her.

Having signed up for a political revolution, Ivan becomes a fugitive in and of his own life. Having enrolled in a marriage, Ivan and Phoebe break apart, not just as a couple, but as people. There are positive consequences: Ukraine wins its independence; Emilia, Ivan and Phoebe’s beloved daughter, is born. But Lutsyshyna’s careful, compelling excavation of all her characters’ desires and motivations, hopes and fears show how vulnerable individuals are to forces like these, to the brute weight of these institutions as they settle on to who we are even as they help us define ourselves—as a student, a wife, a revolutionary, a Ukrainian. She gives us fair warning: even when we seek them out, they may change us in ways we didn’t sign up for.

FICTION

Ivan and Phoebe

By Oksana Lutsyshyna

Translated by Nina Murray

Deep Vellum Publishing

Published June 20, 2023

[ad_2]

Source link